The music of the Caribbean is on the move, its many waves gathering to flood the mainstream of world music – given the chance.

Jamaica’s reggae, carrying a stamp of approval from the American pop music establishment in the form of reggae categories in the Grammy awards, has already captured the world’s attention (thanks largely to the pioneering work of the late great Bob Marley and Chris Blackwell of Island Records). Emerging from the Kingston ghettos 25 years ago, it has spawned many forms from its ska and rock steady beginnings, through roots, dub, one drop, rub-a-dub, lovers rock, dancehall, ragga to bhangramuffin in the UK, and can now boast major foreign exponents like South Africa’s Lucky Dube and Alpha Blondy from the Ivory Coast, as well as surviving Jamaican legends like Bunny Wailer, Third World, Desmond Dekker and Dennis Brown.

But there are other styles of Caribbean music itching to make a similar breakthrough: contemporary popular forms like zouk (already big business in France), merengue, salsa, soca and calypso, traditional folk styles like the beguine and mazurka of the French islands, the Spanish-derived parang and Indian derived chutney of Trinidad.

The front-runners to join reggae in the international mainstream must be soca and calypso, rooted in Trinidad and Tobago and popular throughout the eastern Caribbean. Soca is new-wave calypso, faster with light party lyrics, originally defined as soul-calypso; it borrows rhythms from neighbouring South America and incorporates features from all sorts of other musical idioms (Shango beats, Baptist chants, Hosay drums, rock guitar). The latest version, complete with bogle dance, is a fusion with dancehall.

But reaching the world market means either winning serious contracts with international labels, or establishing a solid Caribbean industry, top-rank indigenous recording studios with real marketing and distribution expertise.

Two major southern Caribbean studios – Eddy Grant’s Blue Wave Studio in Barbados and Robert Amar’s Caribbean Sound Basin in Trinidad – have invested major capital not only to produce top quality calypso and soca products but to back them up with the kind of international marketing and distribution they have not so far had.

With the exception of Arrow, whose Hot Hot Hot has sold over 4 million copies to date, and the Mighty Sparrow, “Calypso King of the World”, soca and calypso have had little success in penetrating international markets. Michael Manley once referred rather unkindly to “the biting but parochial satire of the calypso”, and it is significant that Arrow, who hails from Montserrat rather than Trinidad where calypso was created, was criticised by purists for “discofying” the music.

His answer is simply to point to his success, which beside taking him worldwide earned him the M.B.E. in 1989. “My principal goal is to take soca international, to broaden its appeal so that Caribbean music is enjoyed everywhere.”

Arrow believes, and his fans would agree, that soca “is the ultimate dance music”. Its thrust is even more visceral than calypso. After his reception in South America and Japan, Arrow is convinced that, given the sort of support the Jamaican government has given reggae, soca can make it.

But his own recording schedule points to the problems. Although Arrow used to record in the Caribbean, cutting albums at Kingston’s legendary Studio One and Soca Savage at Byron Lee’s Dynamic Sounds, economic considerations combined with an intensive touring schedule have led him to do recent recordings in New York, where attractive rates are on offer. He admits: “I’d love to record in the Caribbean, but it boils down to dollars and cents, and I’ve worked with people up there who believe in the music.”

Arrow is full of praise for Jamaican studio engineers, but contends that more soca- minded engineers and producers are needed and that soca artists need to educate themselves about record production. “You have to be with your product all the way, from inception to delivery. It’s no good having a brilliant sound and ending up with a bad mix!”

Guyanese-born Eddy Grant, founder and President of the UK-based Ice Records, has already taken several of the steps necessary to market calypso and soca effectively. Now in his mid-forties and with a string of hits behind him (Living On the Frontline, Romancing The Stone, Walking on Sunshine) this son of a Guyanese trumpeter tasted teenage success with The Equals in England before leaving to go solo. In the late seventies he made the move to Barbados, setting up his own Blue Wave recording studio in the converted outhouse of Bayleys, an 18th-century plantation house. The Rolling Stones recently spent several weeks there writing material for their next album.

Fiercely committed to calypso and soca, and appalled at the casual approach to business matters that has hampered the music’s appeal, Grant has been buying up the catalogues and archives of the calypso greats. He now owns the most extensive collection of original works by The Roaring Lion, Lord Kitchener and the Mighty Sparrow, and has signed Trinidad and Tobago’s 1993 Road March King and Soca Monarch SuperBlue to his Ice Label.

Last year Grant signed a distribution deal with the American-based RAS (Real Authentic Sounds) Records. That partnership will be crucial in mobilising calypso and soca: RAS has been credited with the successful marketing of reggae in the United States over the last ten years. Among the big names they have launched are Yellowman, Black Uhuru and Gregory Isaacs.

The deal was struck, Eddy says, because “I know in my heart that soca has the same potential (as reggae) to achieve great popularity in North America, but there has never been the proper commitment to marketing these artists and their music. In the same way Island did with reggae, I want to market soca and deal with it in the best way. It appeared to me that RAS had become the number one distributor of reggae worldwide and … was dealing with reggae as a labour of love in the same way deal with soca.”

The decision to turn the Ice Record label into a “soca entity” is already bearing fruit. For this year’s Trinidad Carnival, Ice released albums by Roaring Lion, Mighty Sparrow and SuperBlue. For Lion, at 85 the oldest living calypsonian, it was his first album since 1957, and on the strength of the phenomenal response to Roaring Lion Standing Proud he is now making a come-back which promises to turn into a second career.

Following hard on the heels of these three releases came the first three volumes in the Caribbean Classics series (Sparrow Volumes 1-3) and a compilation album, 16 Carnival Hits, featuring Sparrow and Kitchener. Sales have been highly encouraging and the American music trade magazine Billboard has hailed Ice as “swiftly becoming the premier calypso label in the world”.

Grant is aware that marketing will take time. “I’m not looking for a quick fix, it could take five or six years before we become anything like mainstream, but in the meantime we must garner respect in the industry and the marketplace.” High on his list of priorities is a campaign to get calypso and soca recognised in the Grammy awards.

If Eddy Grant is impassioned, under his massive Rasta tam there ticks the mind of a pragmatist. He dismisses the idea of a Caribbean recording business, “primarily because there’s no Caribbean record-buying public it’s been eroded over the past 20 years to the point where artists can’t even make a living selling records, it’s futile to consider it.”

His comment may apply to the southern Caribbean rather than to Jamaica, but throughout the Caribbean piracy is still a major problem, whether it is the stealing of rhythms, melodies or lyrics, or theft in the form of the ubiquitous illegally dubbed cassette. This year a new Copyright Act was passed in Jamaica, but legislation has to be seen to be enforced to be really effective. Alain Aumis, the French Cultural Attaché in Trinidad, notes that following police raids several years ago, piracy is virtually unknown now in Guadeloupe and Martinique.

Piracy forces calypsonians overseas to earn their livelihood. Grant muses: “If Trinidad is the land of calypso, where the hell are all the calypsonians?” He feels it is time for governments to step in and follow the example set in the French islands: “There is a business in the offing and lots of foreign exchange to be won from the music if the governments would implement a total anti-piracy campaign.”

Blue Wave, in its idyllic St Philip setting, was originally built by Grant in 1981 for his own use. But his friends had other ideas. Marcia Barrett from Boney M was the first in a succession of artists attracted to its ambience. Others included Musical Youth, Sting (who recorded his first solo album Dream of the Blue Turtles there), Mick Jagger (Primitive Cool) and Elvis Costello. There are perennial visits from Touch and Exodus of St Vincent and Barbadian calypsonians Gabby and Grinder.

An indefatigable and perfectionist producer as well as a talented all-round musician, Grant will disappear into the studio for months at a time to work on his own or other artists’ projects. He speaks lovingly of last year’s sessions with Roaring Lion, who would spend 14 hours at a stretch behind the mike.

In terms of regional studios and foreign artists he insists that “the only thing we have to offer is ambience; anybody can buy technology. The Rolling Stones don’t come here for the technology. Any time an artist thinks of coming to the Caribbean it’s to free his soul. This is a healing place, it clears the vision.” For him a recording studio is “a spiritual place where people convene to emote, to let go their spirit to the world, and therefore one has to create a sanctity about the place that draws people into making things that are spiritually uplifting and ultimately rewarding.”

Grant is critical of the contemporary “clonable” sound, preferring to “deal with sound organically even when using hi-tech, to personalise it and humanise it,” and wants to develop an identifiable Caribbean sound “the way Jamaica used to have a distinctly Jamaican sound from the sixties to the eighties.”

Further south, Robert Amar, a high-profile Trinidad businessman whose interests range from cars and tourism to the local franchise for Pepsi, surprised the international recording business when he opened his US$10 million state-of-the-art Caribbean Sound Basin (CSB) in 1990. The American magazine Mix commented approvingly: “CSB represents a rare sight in these troubled economic times: a newly constructed, fully loaded music recording studio.”

Experts currently rate CSB as one of the three best-equipped studios in the world. It is the realisation of Amar’s dream “to offer both local and international artists state-of-the-art technology in every step of the recording and marketing process.” Amar promises to deal with “all dimensions of the local music art form in its broadest sense: soca, chutney, steelpan.”

With the exception of Blue Wave, CSB is the only prestige studio that can compete in size and equipment with studios like Byron Lee’s Dynamic Sounds or Rita Marley’s Tuff Gong in Kingston, Jamaica. Hurricane Hugo in 1989 virtually wiped out George Martin’s Air Studio in Montserrat, where Paul McCartney, Stevie Wonder and Sting had all recorded.

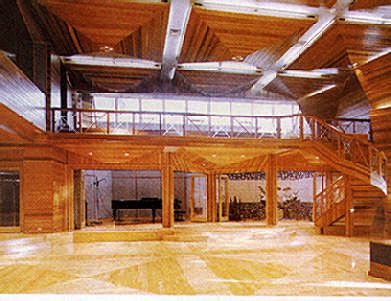

Located in Maraval, an upmarket suburb of Port of Spain, CSB is a purpose-built studio complex housing three separate studios as well as hospitality facilities: swimming pool, gym, sauna, photographic studio and bedroom suites. A recording package offers the use of the company plane or yacht for trips to the sister island of Tobago. As if to echo Eddy Grant’s thoughts on Caribbean ambience, the interior of the complex is spacious and flooded with natural light, in contrast to the darkened norm.

CSB’s three studios are named after Robert Amar and his two brothers. The main studio, Rob, was designed by Sam Toyoshima and John Flyn of The Acoustic Design Group in London. With its 64-channel SSL 4064G console, three isolation booths (vocals, piano and drums) and a massive performance area (60 by 70 feet, and 18 feet high) large enough to accommodate a full-size steel band, Studio Rob elicited a rapturous response from Mix: “Its woodwork and appointments are of an intensity and complexity that suggest religious fervour. ” The room feels like a shrine to the pan drummers and calypso rhythms of Trinidad.”

Studio Rick, designed by Kronos Acondicionmientos of Venezuela, complements the main studio, offering a 48-track Neve console with flying faders, and a more intimate design. Studio Rawl upstairs is a smaller facility with an Amek BC2 console. CSB offers both analogue and digital technology in addition to instruments, a record pressing plant, a disc mastering room and tape duplication facilities.

Like Eddy Grant, Amar is well aware that a studio needs more than technology, no matter how sophisticated, to gain international status. He is hoping to capitalise on the twin attractions of the CSB’s tropical ambience and Trinidad’s rich and diverse culture.

CSB has been wooing international artists, and to date has attracted acts like the cutting-edge American R&B group Tony! Toni! Tone! Their Son of Soul album, recorded live at CSB last summer, has been given unprecedented promotion by Mercury records, hoping to launch the Tonys into the big time in the wake of their 1990 Platinum success with The Revival. Kassav, the leading zouk band, recorded their latest album at CSB; released in April, it went gold within three months. Mick Jagger toured the studio last year with a view to cutting the next Stones album there, and as word spreads so do the prospects of more international business.

Amar Entertainment, CSB’s parent company owns two record companies and labels (Lamar for international music, Kisskidee for local and regional artists), and has launched a series of local promotional tours aimed at exposing young artists. The Kisskidee Karavan highlights General Grant, commander of Trinidad dancehall, whose unique “Binghi” style has already carried him into the Billboard Hot Rappers charts. Four full-page advertisements in the Billboard reggae supplement last July attest to Amar’s confidence that the General has real potential.

A distribution deal signed with America RaRa Records, who like RAS are committed to marketing Caribbean music, promises to give Kisskidee artists, including heavyweight calypsonian Shadow, vital American exposure. The partnership is yet another step in Amar’s plan to build the necessary infrastructure to market Caribbean music worldwide.

A four-hour flight away from Blue Wave and CSB, Jamaica has one of the highest concentrations of recording studios in the world, and produces more music per head than anywhere else on the planet. Though there are at least 12 major 24-track studios and a host of smaller operations as well as private studios, recording time is at a premium, and artists tend to record where time and space are available. Foreign artists are still drawn to the island to capture the authentic reggae or dancehall sound; UB40 were there recently, and Billy Ocean‘s latest album was recorded at Gussie Clarke’s Music Works, one of the hottest studios in Kingston.

The oldest studio complex and possibly the largest in town is Byron Lee’s Dynamic Sounds. Lee, who has made his name and fortune from playing soca at the Trinidad Carnival and around the world, bought out West Indian Records when they went into liquidation in 1968 and began a business which is highly respected to this day. Dynamic Sounds is a survivor of the early era of legendary studios, Channel One, Joe Gibbs, Studio One, King Tubby’s, Harry J, The Black Ark and Tuff Gong.

Sylvan Morris, known as the “dancing engineer”, has been resident engineer at Dynamic for the last five years. He began his recording career there back in 1964 before moving on. He operates in a cluttered workshop, and easily recalls the early days of recording on a 2-track machine. “We’d record the drums and bass on one track, rhythms on the other. After mixing in the console we’d transfer everything to one track and then add vocals.” Ah, the simplicity of the good old days!

Morris has worked as engineer and producer with virtually all the reggae greats, Burning Spear, U-Roy, Big Youth, Delroy Wilson, The Heptones, Ken Booth, Horace Andy, Marcia Griffith, Third World, not to mention Bob Marley and the Wailers. “Right after Catch a Fire I began recording their other albums starting with Rastaman Vibration. I was strictly their engineer at that time and probably worked on about six albums with them.” More recently at Dynamic he recalls Dennis Brown, Freddy McGregor, Lovindeer, Pinchers and the almighty Shabba Ranks.

In the early 70s, as reggae began to reach the world, foreign musicians anxious to check out this powerful roots music of protest and oppression began arriving at Dynamic to record: the Stones cut Goat’s Head Soup there, Joe Cocker followed, as did Cat Stevens before he converted to Islam and disappeared from sight and sound.

Dynamic has recently undergone total refurbishment during which the latest hi-tech studio equipment and state-of-the-art digital recording technology was installed, which in Sylvan’s opinion makes it one of the best studios in the Caribbean.

Not far away on Marcus Garvey Drive is Bob Marley’s legacy: Tuff Gong International, a fortress of a studio crouched behind concrete walls topped with barbed wire. The walls are painted with Marley and Rasta icons: Bob in his favourite Redemption Song acoustic guitar pose, the I-Threes, Ziggy Marley and the Melody Makers, Bob’s mum.

Now run by Bob’s daughter Cedella, Tuff Gong is undergoing extensive modernisation. The morning I went there, it was in turmoil: Ziggy, heir to the Marley empire, and his band The Melody Makers (brother Steve and sisters Cedella and Sharon) had just returned from a sold-out South American tour and were in town for a short stop-over before heading for Europe to promote their new Joy and Blues album. Among recent visitors recording at the Marley shrine are Roberta Flack, Alpha Blondy from the Ivory Coast and Ya Ya of Nigeria.

With dancehall ruling the Jamaican airwaves and making heavy inroads in both America and Europe, the consensus is that the three hottest studios in town are Donovan Germaine’s Penthouse, Gussie Clarke’s Music Works and Roy Francis’s Mixing Lab.

Germaine, who is widely acknowledged as having ruled dancehall for the last two years, manages an impressive stable of reggae stars, including the Crown Prince of dancehall, Buju Banton, along with Marcia Griffith, Tony Rebel and Terror Fabulous. With so much unreleased material on hand in these top studios, security is tight and the unheralded visitor is not exactly welcomed with open arms.

Other popular studios in town are Bobby Digital, Peter Couch’s, Black Scorpio, King Jammy’s and – up on the North Coast in Ocho Rios – Grove, considered by some as the best equipped and maintained on the island.

Scenes outside the downtown Kingston studios are reminiscent of The Harder They Come, the film which introduced Jimmy Cliff and reggae to the world. Knots of young hopefuls gather on the street; my own visit to Lloyd “King Jammy” James in Waterhouse ended in hasty transfer of “nuff dollars” to a yout’ with a gun. King Jammy is famous amongst other things for the 1985 recording of Sleng Teng. With its distinctive computerised sound, this was the record which ushered in the dancehall era and influenced the work of major reggae rhythm-makers like Sly and Robbie, Steely and Clevie, Gussie Clarke and Donovan Germaine.

With pressure on time in all the existing studios, independent producer Rupert Best, who also plays guitar in Dennis Brown’s backing band, notes a trend towards private computerised studios. Computerised recording obviates the need for a master tape with its sound infidelities and is extremely cost-effective.

When called upon by Trinidadian calypsonian Denyse Plummer to produce her latest album for the American market, Rupert found problems at all the available studios and was forced to use different facilities for various stages of production. While admitting “this situation obtains worldwide, I’ve never been in a studio that doesn’t have a problem,” he sees tapeless digital recording as the way to go. His view is shared by top producer Clevie Browne, who see the future as “a combination of man and machine.”

The Caribbean has for years had the skill to make world-class music and to record it well. Reggae has managed the breakthrough; so have a few soca artists like Arrow. What has been lacking is the expertise to steer more artists and products effectively through the tangled web of international marketing and distribution and exposure. Perhaps at last it’s starting to happen.