“Matelot,” people in Trinidad say. “That’s behind God’s back.” By which, of course, they mean that the place is behind people’s back, for, as people know, God was made in the image of man.

And Matelot is certainly behind people’s back, way, way up in the north-eastern corner of Trinidad, where holiday-makers don’t go, telephones just go to die and electricity only pays intermittent visits. A satellite dish that ventured up here a few years ago, armed with all the most modern anti-corrosive features science could devise, was quickly defeated by the powerful sea-blast and is turning to powder.

Yes, progress has met its match in Matelot. It loses its steam as it climbs the hills of the north-eastern coast, past the elegant holiday retreats of Balandra, the turquoise coves and the sea-almond branches, past the turtle-savers’ shrines of Matura and the surfers’ paradise of Toco, past the vanished rural homes with concrete stairways that lead to nowhere like the points of pyramids in the Egyptian desert, past the greying army of abandoned coconut palms on the San Souci estates, past the wide empty curves where waves sweep layered white petticoats over the sand like bélé dancers, past the sunken sullenness of Gran Rivière and up again to the cluster of houses at the top of the hill, the last inhabited hill, the village that was supposed to die along with the others that once studded this coast.

This is the village which held out and argued back when Progress told it that 800 people without Kentucky Fried Chicken – without government interest, without a cinema or a supermarket or even a market – could not survive in today’s world.

“Leave Matelot?” asks a young woman sitting on the steps below the church. “Why?”

She is a walking defiance of all modern prescriptions for health and happiness. At 21, she already has three children. Yet her skin has a glow, her teeth sparkle white and even. She looks like a 16-year-old hanging out at the entrance to a disco. “It nice up here,” she smiles. You look around at the dilapidated buildings and ask what’s so nice about Matelot. She chuckles. “We free here.”

It’s the answer you are going to hear from villager after villager. We free here. Free of what? “It ain’t like in town,” she tries to explain. “In town you have to buy everything. Here, if you’re hungry, you could pass in anybody garden and ask for a hand of fig (bananas). And you could go in the sea and dig some pacro (shellfish). Or get some seamoss. Look at them fellas there . . .”

She points to two men walking up a hill, carrying large oval breadfruits the clear green colour of young iguanas. “That is not their garden, you know. They just ask the owner for some breadfruit to cook. When the boats come in, you could just go and help them pull up and you will get a couple of fish.”

What Matelot people are free of, you realise, is the cash economy. The village motto says: “The Sky, the Sea and the People are One.” Perhaps, where things are free, people also feel free.

“I bought vegetable seeds and taught people how to plant them,” grumbles the Catholic priest responsible for this parish. “When they harvested the vegetables, they gave them all away. They feel food is not something you sell.” She sighs.

Yes, you read right. She. For here, behind God’s back, the “priest” is a nun. The apex of the village is a large church, but the average priest might well go crazy from being stuck up here too long. So ten years ago, Sister Rosario Hackshaw of the Holy Faith Sisters volunteered to take care of the parish.

Possibly she came here to be free as well. As she became engrossed in village life, she soon began to neglect her nun’s headgear. Today, ten years later, having acquired a fisherman’s badge and a large maxi-taxi, she bustles around in trousers, collecting the village’s fish from a cold-storage depot to sell at hotels in town.

She shrugs off questions about her role. “I was supposed to help people here with their problems. If they wait for vendors to come to Matelot, they have to take whatever price they are offered. Sometimes they used to give away carite for 50 cents a pound.” Now, having talked a foreign church charity into funding the cold-storage facility, she gets the villagers to save up the fish for a couple of days till she can career down the winding curves to find better prices.

“The villagers used to tell me, ‘Things will improve, God willing’. I tell them, ‘God always willing. It’s you that’s not.”‘

You hear the sounds of resistance at village meetings. Shortly before I arrive, a young teacher brought in by Sister Rosario mentions Darwin’s ideas on evolution. Revolt is simmering in the houses between bounteous forest and bountiful sea. What about Adam and Eve, everyone wants to know? Theresa, the lady who presides over the village parlour (café), is an avid pentecostalist. In between preparing a meal for Sister’s guest (me) she takes the nun to task for letting loose this monstrosity of a notion. Everyone is preparing for the theological bombshell that is going to explode at the next parent/teachers meeting.

As we sit on the tiny porch behind the Catholic presbytery watching the sea wash over the rocks, Sister marshals arguments from the Bible. “They going to qu-arr-el!” She draws the word out, spooning up some more of Theresa’s excellent fish-and-breadfruit with relish, as she recounts tales of earlier PTA meetings. Debates have been known to end in physical combat and the ripping of disputants’ clothes. Agreement on a design for the school uniform only came after weeks of discussion, as everyone gave their views on fabric, colour and style. Fishermen almost came to blows at the last school sports when the judging of the children’s raft-race was alleged to be unfair.

“You should have heard the row when I had the primary school rebuilt,” Sister says. “They said they had all gone to school in that building and I was destroying their roots. I told them: ‘Sure, you need roots. But you don’t have to sit down on the roots in the manure.'” Except that manure was not the word she used. “Roots need manure, you don’t.”

By contrast, life in the bar at the top of the hill is quiet. “We never had a fight here,” asserts the owner, Raymond. I am sceptical. “The men in this village don’t drink and fight and so on?” I ask the women. They smile in a bemused way, and then generously scratch around their memories for isolated incidents with which they might entertain their visitor.

“You know, long time those things used to happen in truth,” concludes Dee-Dee, a pragmatic thirty-nine-year-old. “I think maybe they don’t have so much money nowadays to buy rum.”

“They don’t beat their wives” She looks puzzled. “Why they will do that?”

I shrug. I don’t know why men should beat their wives. I just know that they tend to, elsewhere. But here it seems that domestic violence is a rare sideshow in the drama of life. Crime rovides only minor entertainment, amounting to nothing more than the occasional theft of a chicken to keep the Sherlock Holmeses of the village occupied. People sleep with their doors unlocked.

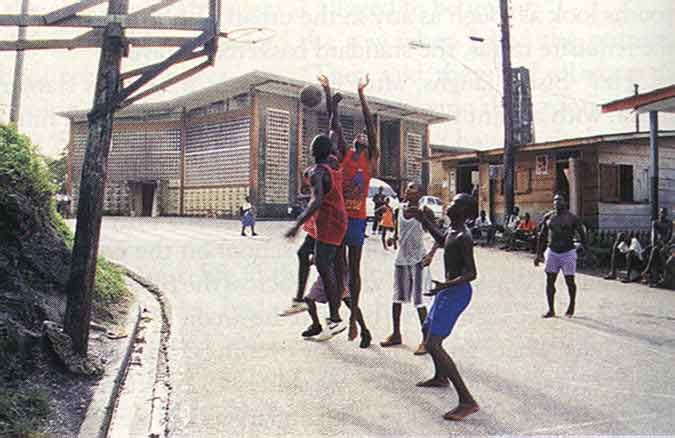

And yet, when you drive into the centre of Matelot, where the church, the parlour and the school form a ring, the lounging youths look as tough as any in the urban Caribbean. There are the requisite rastas, the standard basketball players.

“He?” Sister laughs, after engaging in a raucous slanging match with a giant fisher-youth. “I will ‘fraid he? I beat him in school.”

In fact, school seems to be the secret of Matelot’s peace. The village has two of them, though it contains only about 200 children – the Catholic primary school on the corner and a beautiful wooden secondary school across the river to the north.

Lack of electricity gave birth to the second. “With all these black-outs, what can you do in the evenings?” asks Sister. “One night, sitting in the darkness, we started to entertain ourselves by talking about what kind of secondary school we would want if we could have one. We were tired of doing our best with the children at primary school, and then having to send them out of the village to continue their education.

“Half the time the bus wouldn’t arrive to bring them back in the evening and they would have to walk 15 miles from Toco. They would be too tired to do homework. And they couldn’t get the kind of personal attention from the teachers that they got in the village.

“Electricity didn’t come back that night, so we just dreamed and dreamed about what kind of education we could give the children if we had our own school. By the next day, we couldn’t see any reason not to begin building it.”

There were reasons, of course – lack of teachers, money, official support. But Rosario tends not to see some things, and has a habit of infecting others with her selective blindness. I know this from personal experience, having been subjected to her treatment ten years ago when she first tried to set up a library in the village. She decided that a journalist from the city would be useful to her purpose and abruptly descended on a total stranger with an invitation to spend a fish-filled weekend at the beach. A week later, I found myself begging for bookshelves at a hardware store in Port of Spain.

Today, Matelot has two libraries, God knows how. Or perhaps He doesn’t, perhaps He just turns his back and pretends to look the other way when he sees the light going on in Rosario’s eyes. Which often happens when the electricity company fails to turn on the lights in Matelot.

For that is how Matelot manages to have one of the most modern electricity systems at its secondary school. The authorities were reluctant to extend their services across the river. So Rosario upped and went out and got a windmill from the Catholic Agency for Overseas Development in London. Then Matelot Community School set about making its own electricity.

It also makes its own fishing boats. Matelotian boat-builder Alfred Baldeosingh teaches the kids how, despite the fact that his teacher’s salary sometimes doesn’t arrive for months. A well-built boat commands a good price; especially if you cut down one tree from the forest yourself, that is, and use the right parts of the roots for the inner supports. And if you know how to make the tools for boat-building as well.

People come from all over Trinidad to ask Baldeosingh to build boats for them. He does so under one condition: it mustn’t involve putting a foot outside Matelot. He has been “outside”, he says, living and working in the urban parts of Trinidad. With his woodworking skills he can always find a job. “But in town, it’s like dog behind agouti. You always have to be looking behind your back.”

Here, his children can wander into the depths of the forest without him having to worry about them. They have choices. They can do well in traditional school subjects and become bank managers or whatever, or concentrate on subjects that will enhance the traditional skills of fishing, hunting and agriculture. Experiments in breeding rabbits, chicken, ducks, goats and sheep take place behind the school. Animal food is being produced from fish. Students who have passed their examinations at 15 or 16 get lessons at night from the teachers, so they can go on to the advanced courses. Those who need extra help are put into the hands of Montgomery Charles, a 21 -year-old graduate of Matelot Community School, for evening lessons.

“Matelot has been very good to me,” explains Monty. “I owe a lot to this community, so I want to give something back.” He is a full-time teacher at a school down the coast, but he returns every evening, and functions as president of the village council. “I lived in the city for six months,” he says. “But I couldn’t stand the poverty and crime.”

Isn’t Matelot poor as well? He looks horrified at the thought.

“We have fishing, hunting and agriculture. That’s not poverty. Any community that can feed itself doesn’t have to depend on anybody. We can contribute to the productivity of this country.”

So every child you speak to says she is studying “PoB” and “PoA”, which turn out to be Principles of Business and Principles of Accounts. Boys train in Home Economics along with the girls. And every single child learns Spanish from day one in primary school. Grabbing every “freeness” she can lay her hands on, Rosario encourages young Puerto Rican seminarians to come and help her in Matelot as part of their training for the priesthood.

“When I first came here,” says one of them, “they all thought of Spanish as a monster who would eat them up. They would plead with you not to have to do Spanish. Now Spanish is a friend.”

The school has been so successful that people from lower down the coast, in front of God’s face, are now trying to send their children there. The government is paying unemployed youths from

elsewhere to attend Matelot’s boat-building programme. Fortunately, since they take up the places of the village school-children, they don’t stay. What’s there to do here, they want to know?

“It have a lot of things to do here,” asserts one villager. Like what? She considers. “We have Fishermen’s Fete.” Seeing my expression, she tries to impress me with its joys. “It does be nice! We have we own steelband in the school. And we have we own carnival, with old mas. We does invite all the other villages on the coast to send entrants to our calypso competition. It does all be on politics. Not just Matelot politics, you know, but all kind of politics. And then we have sports – raft race, Iron Man swimming race, relay … ”

And every Sunday it’s like a family day at the river, says the young seminarian. Some play football or cricket or rounders in the space below the school, while the others are swimming. You see girls lugging huge trays of Sunday lunch to the site, then joining the “blocko” on the ghetto-blaster-infested bridge. Those with excess energy go deep into the forest to find the big pools to swim in or to hunt for wild game. There must be a catch, you think. Too many cliches spring to mind: nymphs and nymphets gambolling in glades; the noble savage; man in tune with nature …

“These children have to live in the 21st century,” Rosario worries. “Today, computer literacy is what literacy was to us.

So, if God should only turn his back for a minute or two more, perhaps Matelot might have a computer centre, the same way it got its maxi-taxi practically for half-price from a local vehicle magnate. “What’s next?” you tease Rosario. “The University of Matelot?”

“Well, I was thinking,” she admits, “of a Faculty of Environmental Science. We need researchers up here to investigate what can be done with the resources all around us. How we can preserve the environment while making the best use of it.”

Electricity has been off in the village for the last three days. As you sit in the moonlight, with the sound of the sea behind you, there is nothing you can do except think. Soon you, too, begin to spin out the little dreams that you have stored up deep in yourself behind people’s back.

“You know you’re a great woman, Rosario?” murmurs a visiting Port of Spain businesswoman. The same bemused expression I’ve seen on the faces of all the villagers when I ask my silly questions appears on the nun’s, a look of incomprehension, inability to find words that people will believe at the end of this century of disbelief.

“I just happy,” she shrugs.