Agent 007 – alias James Bond, the bane of international terrorists, megalomaniac scientists and nefarious drug barons – was really more at home on the rugged north coast of Jamaica and its neighbouring cays than in the casinos, clubs and secret service offices of London and Europe. Susan Ward uncovers the best-kept secret of a superagent.

“The name is Bond–James Bond.”

One of the most evocative catchphrases of post-war fiction and film is indelibly linked with the agent who was “licensed to kill”. No matter whether the face you conjure up belongs to the saturnine Sean Connery, the ironic Roger Moore or one of Bond’s other incarnations; to understand our hero we have to track down his enigmatic creator — Ian Fleming.

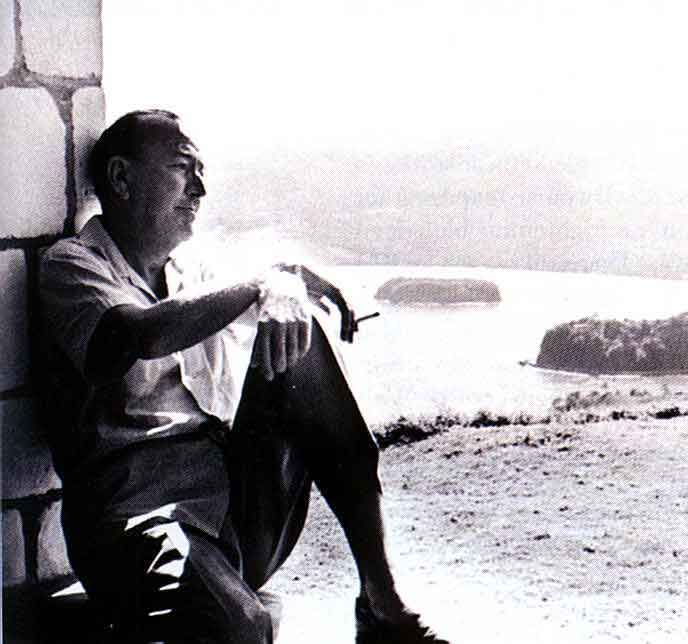

Like the Bond of his books, Fleming smoked 70 cigarettes a day, wore dark Sea Island cotton shirts, and drank stiff vodka martinis. A wartime naval intelligence officer, his experience of the kind of man who could be trusted with dangerous clandestine missions served as inspiration for the adventures of 007. But the lovingly detailed idiosyncracies and the hard-bitten convictions were those of Fleming himself.

One of those convictions was this: there was nowhere else on earth whose lifestyle, people, climate and natural attractions so consistently enthralled him as the islands of the Caribbean — particularly Jamaica. But although several of his novels used the island as background, only two of the Bond movies were actually filmed there.

lan Fleming was a difficult man, impatient and easily bored with social gatherings, yet needing the buzz of the high life and the excitement of travel to stimulate what could seem a jaded appetite. At the same time he was intensely private, devoted to a few close friends, and in periodic need of the rejuvenation offered by silence and an uncomplicated, almost spartan existence. What he needed was a refuge — and from 1945, seven years before his alter ego came to share his life, Ian Fleming found his place in paradise.

He built his Jamaican home Goldeneye on a 14-acre strip of land near the harbour village of Oracabessa, on the north coast of Jamaica. In 1947 he consummated his love affair with the island in an article he wrote for Cyril Connolly’s Horizon magazine. The incipient romantic underneath the man of action emphasised elements of an older, myth-laden culture with its mysterious Cockpit Country where the roads disappear (“The Land of Look Behind”), its fatefully-named Doctor’s and Undertaker’s Winds, and its tales of ghosts and voodoo curses. Jamaica’s politics were treated with indulgence, and its social problems were overlooked in an exuberant paean to its food and natural assets.

It was hard to recognize in this unabashed lover the future master-author of ice-cold, ruthless covert operations.

Infatuation had begun during the latter stages of World War II, when Fleming made the occasional visit to Jamaica as a part of his official duties. It was his immediate boss, Admiral Godfrey, Director of Naval Intelligence, who introduced him to the delights of scuba-diving during an Anglo-American conference there in 1942. This interest soon became a fascination, and in later years his knowledge of Caribbean fish and shells offshore, and of birds and wildlife on land, was impressive.

It was a volume from the Goldeneye natural history library that provided the name for Fleming’s hero. The Birds of the West Indies was a book he always kept on his breakfast table along with his binoculars; its author was a mild-mannered lecturer at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. A letter was sent, asking the ornithologist if he minded lending “his brief, unromantic but masculine name”.

Years later, in 1964, when Bond was a household name, the real James Bond and his wife shared lunch with Fleming at Goldeneye. Afterwards, the two disparate authors were interviewed by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and Fleming inscribed a copy of You Only Live Twice “To the real James Bond, from the thief of his identity, Ian Fleming, February 5, 1964 – a great day.”

Such admiring larceny informed the characters of many of Bond’s adversaries and comrades-in-arms, and the situations in which he found himself. Fleming was an irrepressible scribbler and had a long memory for the quirks of friends and acquaintances. He took a notebook everywhere, and faithfully logged sights and impressions that hit him.

In his earliest book, Casino Royale (1953), little was made of his West Indian connections. Completed in an eight-week burst of manic energy which began on Tuesday, January 15, 1952, during Fleming’s usual winter sabbatical from Fleet Street at Goldeneye, it chronicled Bond’s adventures in a continental setting. Many personalities are credited with colouring the character of the suave special agent, including “Biffy” Dunderdale of MI6, William Stephenson (“The Man Called Intrepid”) and Edward Scott, a former editor of the Havana Post, Fleming’s “man on the spot” for the Sunday Times during Castro’s Cuban revolution.

Bond’s next appearance, however, brought his creator’s island infatuations to the fore. In his notes to Live and Let Die (1954), Fleming states that the underwater chapters grew from his explorations around Cabrita (Goat) Island, near the Jamaican town of Port Maria, where the legendary Henry Morgan — erstwhile pirate, Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Jamaica from 1675 to 1688 — was said to have secreted his ill-gotten gains. Fleming had long been obsessed with the buccaneer and devoted considerable research to the background of the action in the novel, which concerned illegal trading in Spanish doubloons from the treasure.

All this changed when Hollywood filmed its version in 1973. Times had moved on, and the author himself was no longer around to influence style or content. Out went pieces of eight, in came heroin smuggling — a more “modern” and dangerous pursuit for villains, it was thought. Only some of the original characters remained in the celluloid version — among them Baron Samedi, the “real” “King of de Dead” and the most feared of the spirits.

The screenwriter, Tom Mankiewicz, and director Guy Hamilton were responsible for the choice of locations. But at least these were truer to Fleming’s intentions, and brought Jamaican lushness to the screen for the second time. Film sites included Ocho Rios and the Montego Bay-Lucea Highway, where a specially-flown-in London doubledecker bus was cut in half by a bridge during a chase sequence. The elegant and atmospheric San Souci Hotel made an appearance, replete with local fireeaters and tourist extras.

One scene was shot on a crocodile farm/swamp safari near Montego Bay, whose owner, Mr Kananga, became a film star by default, since he was the only man who could jump across the crocs’ backs from one side of the pool to the other (the fact that the animals’ feet and tails were tied down made the feat only slightly less suicidal).

Bond’s first cinematic outing had taken place 11 years before, with the release of Dr No (Fleming’s sixth Bond adventure, published in 1958). During the month-long filming in Jamaica, Fleming visited the set many times, as well as entertaining the director and the young Scottish actor who would become the embodiment of Bond, Sean Connery, at Goldeneye.

Fleming had hoped that his villainous doctor would be realised on screen by his great friend and island neighbour, Noël Coward, but the playwright’s telegram — “Dear Ian, the answer to Dr No is No, No, No, No” — put an end to that. Instead, members of the cast had to make do with generous hospitality at Coward’s Firefly estate.

The idea for the book originated in an expedition Fleming was invited to join to Inagua Island in 1956. During a rugged scientific investigation into the flamingo colony of this southernmost of the Bahamas, Fleming shared a tent with the game warden travelling around in a marsh buggy, later to be immortalised as the evil doctor’s flame-throwing “dragon tank”.

Inagua itself was disguised in the book as Crab Key, the doctor’s fortress isle, although in the film Jamaica played both itself and the Key. The bird dung which Fleming saw everywhere on Inagua was recycled into the guano factory which Dr No used as cover for his counter-intelligence; in the book he ends covered, indeed smothered, in his own bird droppings. As this was hardly an adequate cinematic end for a Cold War baddie, in the film Bond and his current paramour Honeychile escape into his nuclear reactor tank (upgraded from the mere electronics of the book).

The beach sequences were filmed at Laughing Waters, the hideaway of Mrs Minnie Simpson, a reclusive but supportive neighbour of Fleming’s, while the mangrove swamp on Crab Key was impersonated by what is today the Swamp Safari, the place where the crocodiles grinned in Live and Let Die. King’s House and the Liguanea Club (the erstwhile Knutsford Club) were pressed into service for scenes needing an old colonial flavour, and the cement works at Port Royal masqueraded as the doctor’s bauxite mine.

The Jamaican film crew left an indelible stamp on the production, since the songs they sang as they worked were eventually orchestrated into the soundtrack; listen and you’ll hear Underneath the Mango Tree, Jump Up Jamaica and Three Blind Mice.

The Cayman Islander, Quarrel, Bond’s Man Friday in Dr No and several later books, was based on Aubyn Cousins, the son of Christie Cousins, who sold Goldeneye to Fleming. Fleming and Aubyn became snorkelling companions in the bay below the house, and it was Aubyn who showed the writer how to lasso sharks that had been thoroughly enraged by dead meat. This knowledge was put to use in one of the most frightening moments in the Bond canon, when Mr Big whips his “guardian sharks” in Live and Let Die.

Another local, Red Grant, gave his name and huge physique to the assassin from SMERSH in From Russia With Love (book 1957, film 1963). His true nature was happily less sanguine – he was the owner/pilot of a white-water raft on the Rio Grande, whose Strong Bak Soup Fleming shared every winter in an into a feeding frenzy annual trip down the river. It was a voyage which Fleming insisted even his most nautically-challenged guests make if they were to enjoy his Jamaica. Today, three rivers offer a choice of rafting, an essential fixture on the tourist circuit, though the “cheerful, voluble giant” Grant has long gone.

Nearby Drax Hall Estate at Oracabessa gave a name to the arch-villain Hugo Drax of Moonraker (book 1955, film 1979). Here too changes have come — the site is being developed into a huge resort complex and will soon be unrecognisable.

Today’s Jamaica attracts many more visitors than it did when Fleming and Coward could think themselves lost on its northern shore. But respect for the old ways and days is there under the surface — and now Fleming is part of that valued past. It is fitting that Chris Blackwell, the son of Fleming’s neighbour, one-time location manager on Dr No and today the Chairman of Island Records, should have bought Goldeneye. The house stays in the Jamaican family, as its devoted maker would have wanted.