“You’re standing on my paaaaaaintings,” wailed Winston Branch indignantly.

I looked down. What I had perceived to be a large, brightly-coloured rug was in fact a springy pile of canvases, and my feet, encased in a pair of bulky hi-top sneakers, were sunk in the middle of the pile.

I leapt off as nimbly as possible and examined the top painting to see if I had damaged it. I felt as though I had stood on a child.

“I’m so sorry,” I said, horribly embarrassed and reflecting that this was not the best way to begin an interview. “I thought they were a rug,” I added lamely. “They were sitting on the floor in front of the door.”

“I’m shipping them off to an exhibition in Santo Domingo,” the artist explained. “That’s why they’re there. They have to be packed.”

My obvious discomfort at putting my foot in it made him relent a bit. He invited me to examine the paintings.

The top canvas was an abstract frenzy of red and yellow entitled More Flames Than Fire. Beneath that lay Homecoming and Perfect Mother, more abstraction, in predominantly earth tones. The last was a lively painting entitled Forever Dancing. All had been done in quick-drying acrylic, a godsend in my favour. Had I stood on an oil painting, my footprints would have been recorded for eternity, not merely in Santo Domingo.

Branch had just returned from Belize where his work had enjoyed two exhibitions.

Belize, said Branch, had inspired him. He had suffered several months of frustration in St Lucia, and Belize, full of Mayan imagery and bright colours, had recharged his batteries. He was even impelled to buy paints there so that he could interpret his ideas instantly.

As if to keep the inspirational spirit around him all the time he had bought several waistcoats in Belize, all colourfully embroidered with Mayan motifs. He wore a different one each time we met. During our first interview, I noticed four similar ones laid out on his sofa, presents for his family – a family he barely knew. He had lost touch with them 33 years ago when he left the island to further his education.

Winston Branch was born in St Lucia in 1947. At 15 he moved to England; having acquired the necessary qualifications and sufficiently built up his portfolio, he was accepted into the Slade School of Art in London. He was one of 40 successful applicants.

No-one in his family painted, and it took all his courage to stick to his career choice. However, once he had seen the work of the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam and Roberto Matta, the influential abstract expressionist from Chile, Branch knew he could succeed — “They inspired me because they came from my part of the world.”

Although he never met them, the powerful art of Lam and Matta helped shape his vision.

“It takes courage to paint,” Branch says. “You are living on the edge, doing something that no one asked you to do, that no one really wants and you are telling them they ought to have it. It is difficult, you have to be tenacious.”

The Slade gave Winston Branch an exceptional introduction into the art world. By the time he graduated, his work had been shown in British galleries such as the Art Lab in Drury Lane, the crypt of St Martins-in-the-Fields, and the Round House. Internationally, his paintings were exhibited in Algeria and Belgium, and at the Pan African Cultural Festival in 1969. In 1971 he had a one-man show in São Paolo, Brazil, which Branch calls the “second most important venue in the world for contemporary painting.”

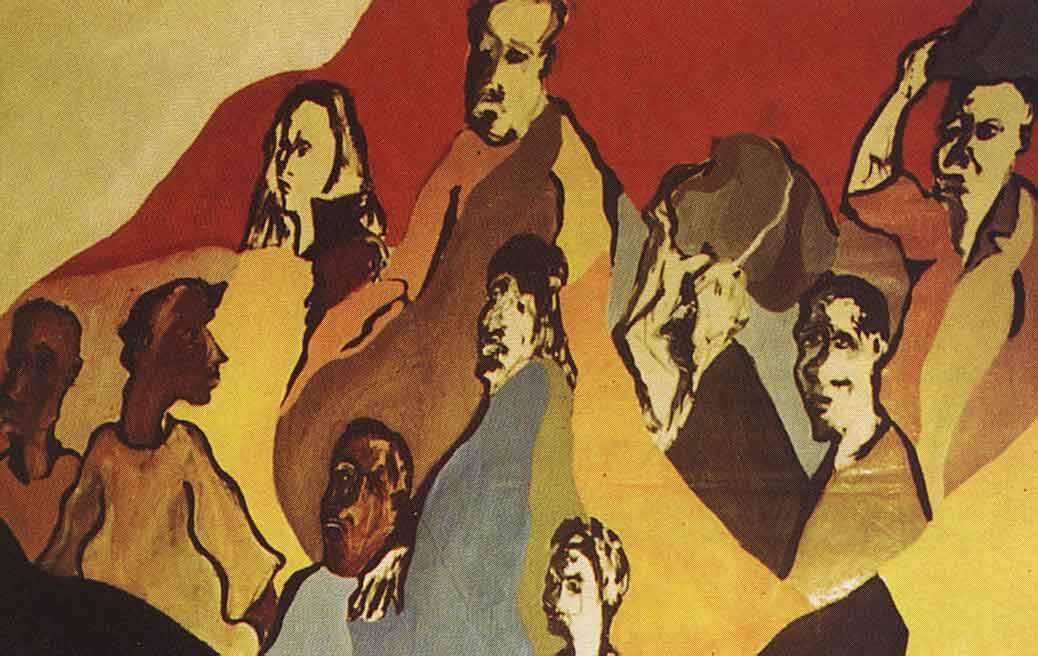

The Museum of Modern Art in São Paolo has one of Branch’s biggest works in its permanent collection. The Children Of The Wretched Of The Earth is a 30-foot piece consisting of three canvases. The first deals with the disastrous fire in St Lucia’s capital, Castries, in 1948; the middle is a melting-pot where figures from the first and third pieces intertwine. The last piece deals with the history of the Haitian revolutionary leaders Henri Christophe and Toussaint L’Ouverture.

At the Slade, Branch sold his first painting for £100. But the first important purchase of his work was by the Contemporary Arts Society, which buys paintings each year from artists predicted to be the artists of the future.

Branch’s work is now in the permanent collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum and the Brooklyn Museum. In England, he also studied stage design and worked on the sets of London productions of George Bernard Shaw’s Village Wooing and William Saroyan’s Hello Out There. He worked on theatre and film sets in Amsterdam too.

Shortly before graduation, Branch won the Prix de Rome, a two-year scholarship to the British School of Rome, an establishment founded in 1851. Branch accepted the scholarship, but he did not want to go to Rome. “Rome was very provincial and backward and I did not want to be there. I absconded after one year and came back to London, which was full of excitement.”

But the scholarship put him one step up the ladder. While he was in Rome, he exhibited in Paris, at the Grand Palais. “Paris was full of art,” he says.

In 1972, Branch returned to London to teach at Goldsmiths College. “That was very dread because it was not what I wanted to do. But there is a kind of false sense of respectability in the British domain. You can’t just be a painter, you have to be an art teacher.”

Once he figured he had acquired the necessary respectability, he moved to Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he was given the title of Artist-in-Residence (“I explored a lot of the deep south and I liked it better than the north”). He finally got to New York in 1973, where he says he “took off”. His two-year stay culminated with a successful show at the city’s Terry Dintenfass Gallery.

Branch returned to London and in 1976 was invited to spend a year in Berlin as part of the Artists in Berlin Programme (Berliner Kunstler Programm des DAAD), which invites artists of international reputation to Berlin to work and stimulate the city’s cultural life.

“They don’t just exchange anybody,” says Branch. Distinguished predecessors included John Cage, W.H. Auden and Igor Stravinsky. Branch spent five years in Germany. “It was very relaxing, without the anxiety of New York. There were no drugs and none of the degenerates who came to ruin it later. You could go out any time of night and find good places for music and food.” Berlin was kind to Branch. He was given a 2,500 square foot warehouse and an apartment. The British ambassador and his son, along with Her Britannic Majesty’s Military Government in Berlin, collected his art.

Some found his work a little mystifying. German Professor Dr Johannes Gerloff said in 1977 that it was “difficult to analyse the effects of Winston Branch’s paintings. The total abstraction that is manifested above all in his most recent pictures shown in Berlin makes it difficult to comprehend the approach, and the titles of the works don’t help much. The viewer must find his own way.”

Branch’s retort is that “I am not about illustration, I am about painting.”

Jules Walter, another German art expert, felt that Branch’s art was an act of bravery. “He has always shown a keen sense of endurance and never fails to take on any task that his art has led him to.”

While in Germany, Branch was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship. This allowed him to work for a year without worrying about money. One condition of the Guggenheim is that recipients spend part of the year working in America. Branch returned to New York and set up a loft at 640 Broadway.

The award gave him instant celebrity. But the pressure was unbearable, and under severe emotional stress, the result of a difficult love affair, he ran from the city. “New York wanted me to stay permanently, but I did not want to. I go crazy when I feel that I can’t come and go as I please.

He escaped to London, and in 1985 rented an old four-storey warehouse in East London that he named Polly’s Palace after his daughter. In 1986 he joined the Caribbean Express, an art show on a train that travelled all over England exhibiting West Indian paintings, literature and music.

From Polly’s Palace, Branch re-established links with St Lucia.

He was asked to contribute to Project Helen, the St Lucia National Trust programme to build a national art collection. When he travelled to St Lucia with his work, he decided to set up a base on the island. “Why do I always have to take winter? Why can’t I enjoy the fruits of my home too?”

St Lucia has turned out to be an excellent place to paint; but Branch finds the Caribbean market small and underdeveloped. The total abstraction of his work is often misinterpreted. In order to sell his work, he maintains strong links with London. Even in Europe and America where people are more receptive to different art forms, paintings are still a hard sell.

“There are more artists than dealers, and dealers don’t want artists because they have to sell what they have already. It’s like coal to Newcastle. Once a dealer is making money, he’s happy, but if he has to push you, well, he’s got 16 like that already and he’s waiting for one of them to die in order to offload his work,” declares Branch.

Often, he complains, an artist’s popularity has little to do with his talent. Getting along in the art world depends as much on diplomacy as on ability to paint.

“It’s all whim. The same way they can like you, they can write you off, so you have to be careful how you tread. It’s business at one level, diplomacy at another, and good manners all the time. Don’t get airs and graces because you can piss people off and then when you find out who they are, it’s too late because they know what you are.”

Branch’s way of ignoring the anxiety of whether or not he is the artist of the month is to shut himself in his studio and work. “I am inspired by getting up and doing the work. You have to get up every day and do it. I got that discipline at university. I don’t go to bars and pick up women, I paint, that is why I have been productive all my life. It is a lot of up and down, but you have to push it.”

Branch paints almost exclusively in acrylics.

“Oil painting takes about 100 years to dry. Now you are up against time and you have quick-drying paints such as acrylic. With oil it would take about a year to do one painting.”

He hates repetition, and after a very brief stint as a portrait painter in his early days, his work is now purely abstract. Art critic Carlos Diaz Sosa describes his paintings as “abstract canvases in cool, cloudy colours that have a quality which allow the viewer to explore the depths of the mind. Branch uses paint like a symbol, a purely aesthetic language, an illustration of spirit.”

Despite opportunities to live comfortably as a salaried art professor, Branch has always preferred to live on the edge. “I have always wanted to paint and I have always enjoyed it. It is kind of foolhardy but that is how I have been functioning all my life. That is all I have done and I try to do the best I can,” he says.

After three long interviews with Winston Branch, the troublesome vision which was locked in my head — a vision of my feet stuck in the middle of More Flames Than Fire — began to fade.

I apologised for the last time. He replied that he could quite well imagine how I might have mistaken his paintings for a rug.

“However, when I go to anyone’s home,” he added severely, “I would never dream of treading on the rug.”