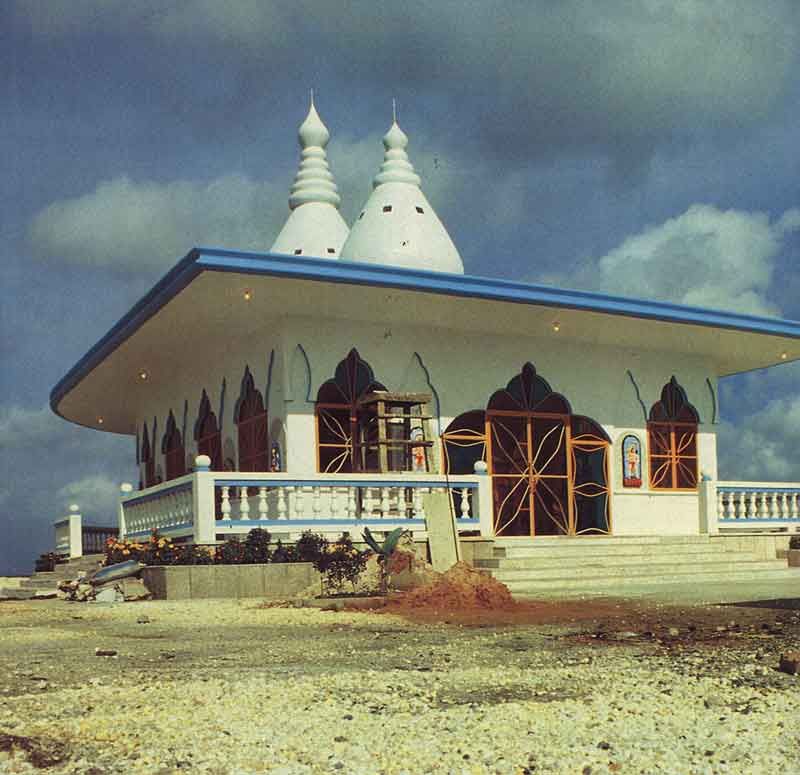

Quarter of a mile off the west coast of Trinidad there stands an extraordinary monument to the human spirit: a magnificent Hindu temple, completed and consecrated at the end of 1995, standing in the sea. It bears the name Sewdass Sadhu Shiv Mandir, and its history goes back far beyond the celebrations of last December.

For many years, an earlier Hindu temple, at the end of a causeway, withstood tides, breezes and neglect. It was the creation of one man — alone, unaided and ridiculed, his largest tool an ordinary bicycle.

“Engineers does want to know how he did it,” said a resident of the nearby village of Waterloo. “He got oil drums from Lever Brothers, filled them up with concrete and tied them together with steel. That was how he made the foundation.”

But the real foundation was tenacity. It led Sewdass Sadhu, a poor indentured labourer from India, to defy not only the elements but the authorities in colonial Trinidad in order to create a place of worship.

“That man went to jail for that temple,” a villager known as Mr Sheik declared. Mr Sheik — whose real name was Ibrahim Khan — died some years ago, in his eighties; but when I met him, he was still full of admiration for Sewdass Sadhu.

Sadhu was the least jail-going type in the village, a hardworking sugar-worker born in 1901 in the holy city of Benares on the River Ganges. “He was not a talker,” Mr Sheik recalled. “If you and he stay together for hours you would hardly hear him talk. You had to do all the talking. He neither smoked nor drank.”

The one thing that made Sadhu noticeable was that he saved his meagre wages and went back to India every few years to worship at the holy shrines there. “I once asked him why he went back so often,” said Mr Sheik. “He said he had made a promise to Bhajiwan (God) to return.”

But as the years passed, the cost of the trip rose. It became more difficult for a labourer working for around $20 a month to keep up this regular pilgrimage. So he decided to create a holy place in Trinidad instead, by the calm Gulf of Paria. “I believe the sea here was like the Ganges to him,” one of the villagers said.

Sadhu chose a piece of unused swamp land close to the shore and began construction. It continued month after month.

“Seven days a week he used to pass my house on his bicycle,” Mr Sheik recalled. “I used to call out to him, ‘Salaam, salaam’ and he used to reply, ‘Ram, Ram.’ He wasn’t the kind of man to stop and blag, you know.”

But Sadhu finished his temple, and the result was a place of renowned beauty.

“You know that flower, gaandar kapoor?” Mr Sheik asked. “He planted so much of it that you could smell the temple from a distance. He planted eleven kinds of flowers, and vegetables too. And that garden used to be full of the most beautiful butterflies. All kinds of butterflies that you don’t see anywhere else. You didn’t have to be one of the Hindu faith to feel the beauty of the place.”

“Especially for Kartik (the festival of the sea), we used to have crowds of people here,” another villager remembers. “They used to have three day-festivals. People used to come and stay and cook and sing … ”

Sadhu had finally created a place of pilgrimage for Hindus in Trinidad, which had few public temples at the time.

That was in the late 1930s. But then the management of the sugar company, who owned all the land in that area, noticed that a building had been constructed on their property. Though the swampy ground had no commercial value, they demanded that Sadhu demolish the temple.

That was asking him to commit a sin. No matter what threats they used, all he would say was, “I cannot break down that.”

They took the matter to the court in Port of Spain. Sadhu was fined $500, more than two years’ wages, and was sentenced to 14 days in prison for trespassing. He had to pay the fine in instalments.

“He make a jail.” Just thinking of it, Mr Sheik burst into tears. “Sadhu was such a soft man, and he make an honourable jail rather than break the temple.”

The sugar company was granted a court order to demolish the temple. But since they could not persuade any local person to undertake this task, a British overseer named Gunn, “a large red-faced man” according to Mr Sheik, drove the bulldozer that finally wiped Sadhu’s creation from the face of the earth.

According to some accounts, Sadhu warned Gunn, “Just as you break that temple with that bulldozer, so you too will be broken.” Others say he just pleaded quietly with the overseer. Whatever the truth, within a month, Gunn was dead. As he was bulldozing a tree some distance away, it fell on him and broke his back. In addition, stated Ramnarine Binda, a former local government councillor for the area and a sugar company official, the Englishman who had given the order for the demolition died suddenly of disease soon after.

As soon as Sadhu was released from prison, say village reports, he was back at the site of his former temple, dejected but not broken. He set about purchasing a truck. He began to collect broken bricks from a nearby brick factory. He dumped them on the shore, day after day, load after load, in a straight line out to sea. Flattening them down by hand, he inched his way into the ocean with the truck. After several weeks, he had created an extended walkway into the water.

Visitors were intrigued. “I used to have two fishing trawlers,” Mr Sheik said, “and I used to be at the same spot in the evening waiting for them to come in. I used to watch Sadhu working for three-four hours out there in the sea.”

One day the tide came up while Sadhu was still working. The truck was trapped and couldn’t be moved till next morning. It was so badly damaged it couldn’t be repaired.

“You would have thought that would stop Sadhu.” Mr Sheik raised his eyebrows. “But no. He just continued working. He would put two buckets onto the handlebars of his bicycle. In one he would have cement, in the other, sand. And he would wheel those buckets out along the walkway he had made, day after day. That is how he built that mandir. I am talking about one man, not six men. He did that for more than a year.

Sadhu was building, not just a temple, but an entire prayer complex, with three mandirs, a kitchen, a dining room, a restroom and another room. Around the whole thing ran a verandah.

“We used to say the sea will wash away everything,” Binda said. “Sometimes I used to pass and see him up to his waist in water, building. We all laughed at him, I included.”

But once the project was completed, it became the focus of admiration for visitors from far and wide. Hundreds of people came for days and weeks at a time, especially at Kartik and other important Hindu occasions. The sea rang with music and prayer.

“I used to go down the islands with my trawlers,” said Mr Sheik. “And quite from the Bocas I could see Sadhu’s kootiah, white and beautiful in the distance. You could use it as a guide to go home.”

Sadhu, too, finally went home, on his last pilgrimage in India before he died in 1970 of a heart attack. But before that, villagers say, he spent many happy hours in his temple.

For a while, the fruit of his faith was left in the hands of the sea, a fact that grieved Waterloo villagers of all faiths and races. Not only Hindus felt strongly about it. “I am a Muslim,” thundered Mr Sheik, “and this is a Hindu business. But it is hurting me to see the destruction. A man make an honourable jail for that temple. You mean to say we can’t keep it up”.

But Mr Sheik got his wish. In 1994, work on reconstructing Sadhu’s temple began, restoring it as a place of worship, a place of beauty and dedication, a shrine and monument to the spirit of a remarkable man. Eighteen months later, on December 10, 1995, the Sewdass Sadhu Shiv Mandir was consecrated, with Sadhu’s remaining family among the large crowds.

In a sense, Sewdass Sadhu himself watched the festivities: for a handsome statue of him now stands upon the shore.

Research assistance by Sean Drakes and Floyd Homer