“Yes, there are meant to be two-line breaks between the paragraphs here.”

“OK, Ismael, we’ll discuss that next time.”

“Well, if there is a strike, you’re not going to be able to get the flight on to St Kitts.”

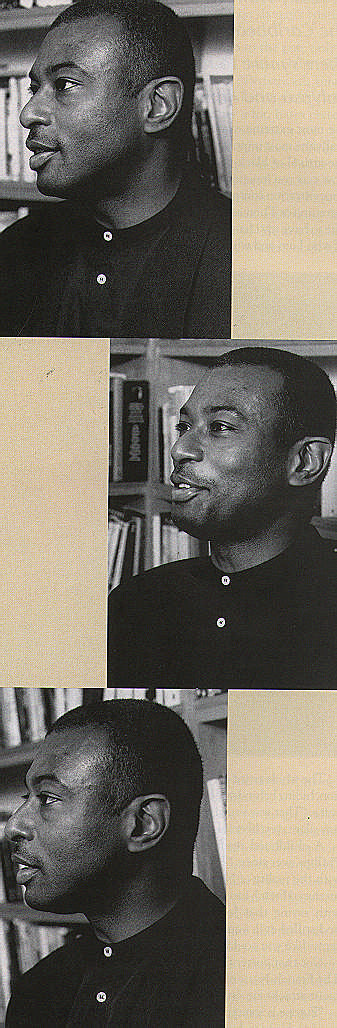

The mobile never stops ringing at Caryl Phillips’s house. And he always answers it, although he says he won’t next time. It’s his American publishers wanting to query some proofs. Ismael Merchant (of Merchant and Ivory fame) calls to arrange another meeting. Phillips’s mother rings again with the latest on her flight to New York.

At least it gives me a chance to look around the sitting room of his small West London house, littered with albums by Ray Charles, Otis Redding and Richard Pryor. Apart from the piles of LPs, it’s the sort of empty bachelor minimalism that married men and fathers can only dream of. On one wall is a 17th-century French map of St Kitts, on another a watercolour by his friend Derek Walcott. “I just asked him for it and he gave it to me,” says Phillips.

The insistent mobile is a symptom of Caryl Phillips’s current success. His latest novel, The Nature of Blood, has just been published in the UK to rapturous reviews. The publicity machine is in full gear, with media interviews and bookshop readings around the country. Then it’s off to the US for two weeks to do the same promotional work for the American launch of the novel.

I ask about St Kitts, which Phillips left in 1958 when he was six months old. His parents came to work in England and it wasn’t until he was 22 that he went back to the island and his parents’ village. “At first I thought, ‘I couldn’t have come from here’. Here I was in this tiny ramshackle village, St Paul’s, the complete antithesis of the metropolis. I had just finished at Oxford and it was real culture shock. I couldn’t relate to my cousins at all. But then I realised that it was my problem, not theirs. I was the one with a funny accent, I walked too fast, wore too many clothes. I had to learn a lot.”

Phillips was in St Kitts frequently during the 1980s, a period which produced his first two novels. The Final Passage (1985) tells of a young couple’s bid to escape a dead-end life in a small 1950s Caribbean island and their disillusionment in a grey, cold London. A State of Independence (1986) follows a middle-aged West Indian man’s return to his home island after 20 years in England.

How autobiographical or biographical are these novels? “In The Final Passage I wanted to pay tribute to my parents’ generation, to say ‘You people really mattered’. In a way, they were real pioneers and I feel a responsibility to tell the third generation, young kids, what is was like to arrive here.” Phillips’s parents, although separated, are still both in Britain. “I think my father’s the only black man in Lincolnshire, still a pioneer.”

This sense of being different, of not fitting in, crops up a good deal in Phillips’s work and conversation. His parents settled in Leeds, “not in a West Indian area, but in a hard, working-class part of town.” He encountered racism early on and could never understand it. “Because I was the only black kid around I thought they were having a go at me personally. I didn’t realise it was about all black people.” When his music teacher called him a “sambo”, he hit him.

Leeds gave him a solid Yorkshire accent, taught him how to fight (and run if necessary) and left him a lot more streetwise than most of his contemporaries when he arrived at Queen’s College, Oxford, in 1975. He had been a bright pupil, supported by his mother and encouraged by the more enlightened teachers in his grammar school.

But Oxford, socially at least, was a let-down. “The other kids were all public school boys and didn’t share my sophisticated interests in beer, women and football.” He swapped from psychology to English, worked hard in his final year and got a good degree.

He thought about staying on to do research and maybe getting into the media. “I was going to do a doctorate about black people in the eyes of the British media. I went to see this guy and he said, ‘Why write about it, why not do it?’ I came out and thought, ‘He’s right’.”

A year on the dole in trendy, fringe-theatre Edinburgh followed. “I decided I wanted to write before I’d written anything.” Phillips started with plays, and three were published by a small press in the early 1980s. He had to practise, he says, for five years before he wrote anything he felt happy with as fiction. During that time he identified with black Americans like James Baldwin and Richard Wright more than Caribbean writers. V.S. Naipaul was the exception. “The Mystic Masseur and A House For Mr Biswas, I loved them. They were about inner-city strife, poor people surviving, both funny and sad.”

Having served what he calls his “apprenticeship”, Phillips sent the manuscript of The Final Passage to the prestigious Faber and Faber publishing house. “It wasn’t entirely unsolicited, thank God, they knew who I was.” It was the beginning of a long relationship with his current publishers.

Like many writers, Phillips bemoans the way in which the publishing industry is now dominated by a handful of all-powerful conglomerates. “Once there were about 20 decent publishers in the UK, today four at most.” He had a brief flirtation with Viking (Higher Ground) and Bloomsbury (Crossing the River) in the early 1990s, but has since returned to Faber. He says they have a good track record on publishing Caribbean authors — Wilson Harris, for instance, and Derek Walcott.

Faber have also had the good sense to appoint Phillips as a commissioning editor, in charge of a new Caribbean list. “I want the very best,” he says, “and that means looking beyond English-language writers and seeing what’s happening in French, Dutch and Spanish as well.” The job involves finding between four and six new titles a year, and so far he’s got books by Aimé Césaire (Martinique), Maryse Condé (Guadeloupe), Antonio Benítez Rojo (Cuba) and Wilson Harris (Guyana) in the pipeline.

Caryl Phillips talks with unusual seriousness about his editing role. “I really want to change people’s idea of the Caribbean and show them that there’s more to its cultural life than calypso and limbo dancing.” He’s critical of the Anglocentric view which defines Caribbean literature as Walcott, Naipaul and not much else. “There is some truly great work from the English-speaking Caribbean: everything by George Lamming, Kamau Brathwaite’s poetry, Sam Selvon’s Lonely Londoners is a complete masterpiece.” But, he insists, there is also a significant literary tradition in islands like Martinique and Guadeloupe, Aruba and Curaçao, that we hardly know about.

The phone call about his proofs brings us back to the current novel, The Nature of Blood, about which he’s recently had to face a lot of criticism. What about the charge that a British West Indian can’t possibly understand the uniquely Jewish experience of the holocaust? He releases a few choice expletives, then adopts the more pained tone of someone who’s explained this point rather too often.

“Look, anti-semitism has fascinated me for thirty years. It’s the most extreme example of racism in Europe’s history, and really the most important model of European race hatred before the arrival of black people here. It’s simply naive to say, ‘Oh, how can you imagine what it’s like to be a Jewish woman in a concentration camp?’ Where does that leave Tolstoy and Anna Karenina or Thomas Hardy and Tess? Anyway, I know what it’s like to have my identity under daily scrutiny, to be hugely aware of who I am and who I’m not.”

The whole point of fiction, he says, is imaginative self-projection, hiding behind and becoming a character, taking on his or her voice. “That way you give a voice to people who would otherwise stay silent, you liberate them from being written out of history.”

A childhood reading of Anne Frank’s diary has haunted Phillips ever since. “I feel an incredible numbness when faced with the reality of Nazism and the holocaust. In an age which produced Freud, Einstein and Marx, how could anyone get away with saying that Jews are inferior?” Nazism was pure hate, undistilled evil; you couldn’t explain it in rational, economic terms like you could African slavery.

Not that current events in Europe fill him with optimism. The French National Front has recently won a local election, racist attacks are on the rise in Germany and elsewhere.

“Europe is sometimes a scary place, I suppose. I’m not totally comfortable here, but neither am I prepared to detach myself from it. It’s a mix of commitment and depression on my part. I want people to realise that European history is a bit more complicated than Agincourt and country houses, that it involves confronting the fact that someone like me is here because of slavery and empire.”

Does this painful awareness of Europe’s past mean that he’d be happier living in the Caribbean? “Well, I suppose the academic chaps would say I’m a product of the diaspora, rootless, not really at home anywhere. But the Caribbean is where I feel most comfortable, where I think I see my point of return.” The islands, he thinks, have a “hybrid nature” — “they embrace Europe, Africa and a lot more besides.”

A recent trip to half a dozen Caribbean countries was, Phillips says, “incredibly liberating . . . I went back with no expectations, no sense of culture shock, just a general feeling of belonging.” His close association with St Kitts is, temporarily at least, balanced by a fascination with other islands and cultures.

He has sold his house at Frigate Bay, although he can go and stay with friends and family any time. “There was too much water under the bridge, I wasn’t spending enough time there.” He has just been to Barbados, and visited George Lamming on the wild Atlantic coast at Bathsheba. “It was a million miles away from the tourist resorts, a superb place.”

As his reputation grows in Britain and the US, the comparative anonymity of being in the Caribbean has its attractions. “It’s a literate society, but not a literary one. Few people read novels and it’s sometimes a relief that nobody knows what I do for a living. But there again, it can be frustrating, and I end up wishing the governments could put more into the arts and education.”

In the meantime, Phillips says, Shepherd’s Bush is about as close to the Caribbean as you can get in Britain, and he wouldn’t choose to live anywhere else. “My neighbours are Jamaican, Greek and Indian, every single pub round here is Irish, there are three Caribbean restaurants within walking distance. It’s what you might call multicultural.”

This idea of being in Britain but not really being part of it seems to epitomise Caryl Phillips. “England nurtured me, gave me my education, shaped me as an individual and a writer. But the Caribbean produced me. It wasn’t an accident of birth, but a fact of history. I try to hang on to the idea of being a West Indian writer first and foremost. And I don’t want to be embalmed on some literary pedestal. I want black kids here to grow up thinking, ‘If he can be a writer, then so can I’.”

The ideal of encouraging, of showing by example, isn’t just rhetoric. One semester each year Phillips spends at Amherst College, Massachusetts, teaching creative writing. It’s a chance to recharge batteries, see friends on the academic-literary circuit and indulge his fondness for American motels. He is currently buying a place in Manhattan, so often stays at a motel near the campus, where the rooms are big and empty. More anonymity, more rootlessness.

It looks like the phone is going to ring even more over the next few years if he continues working at the current rate. In late 1998 Merchant and Ivory are due to film Naipaul’s Mr Biswas on location in Trinidad with Phillips’s script. And he’s already working on a new non-fiction book which will explore three places — Liverpool, Charleston and Elmina on the west coast of Africa — “three points on slavery’s triangle which have tried to silence their own history.”

Finally, we abandon the mobile and go to the pub, only to find that it’s no longer Irish but part of a theme chain. Even Shepherd’s Bush is becoming gentrified. “Perhaps it’s time I moved upmarket to Chiswick.” he says in what might be a joke. He uses irony and self-deprecation rather a lot, hates pretentiousness, keeps you guessing whether he’s serious or not.

It’s a healthy instinct on the part of a writer whose work deals in some of the more harrowing of human experiences. In fact, it’s sometimes as if he’d rather switch off altogether from discussing the novels and their personal heart of darkness. You have to keep drawing him back from talking about something less intense, such as the fortunes of Leeds United. He says reading about the holocaust gave him recurrent nightmares, made him feel physically sick. You feel it’s a subject which is hard enough to write about and almost too difficult to discuss.

Persecution, alienation, rootlessness, the seemingly endless capacity of humans for cruelty: these are Phillips’s recurring themes, explored through a range of historical and contemporary events. He is, in the deepest sense of the word, a serious writer, but never one who descends into obscurity or didacticism. In an age which increasingly equates fiction with escapism, Phillips’s novels offer no easy solutions and few happy endings.

But it is precisely the strength of his fiction and the mark of his growing stature that he compels his readers to confront their collective history. Neither moralising nor sentimental, his writing challenges amnesia and complacency. It is ultimately liberating (this is Phillips’s most used word) because it frees us from forgetfulness and reminds us insistently of our own debt to freedom.