Imagine you’ve booked a holiday. You’re off to the Caribbean; maybe visiting friends on another island. But when you arrive you find your destination has mysteriously changed. It’s an island all right, and it’s hot, and you can hear bass notes thumping reggae-style over the aircraft engines. But it’s not Trinidad, or Jamaica, Barbados or St Lucia . . .

The airport building, however, is painted in familiar colours: red, gold, and green. Inside, you find an unusually pungent scent in the air — though, of course, it may be quite familiar. You look around for a no-smoking zone. There isn’t one. But there is a great selection of places to eat: plenty of vegetarian snacks, no salt but very tasty. Dozens of paintings adorn the wall along one side of the concourse: reggae singers — Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Burning Spear; and famous civil rights and black nationalist heroes — Mandela, King, Marcus Garvey. The remaining walls, from floor to ceiling, are murals: the eastern wall is dominated by an enormous portrait of His Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie I gazing out of Africa, and a panorama of Biblical history spreads halfway around the terminal. Instead of “Have a nice day”, it’s “Jah guide” as you head out to your hotel.

Dreadlocked customs officials, councillors and traffic policemen of every race; ganja legalised as a sacrament; no hard drugs, no violence; absolute freedom of worship for any religion; racism stamped on; a national obsession for knowledge and debate; the greenest, most environmentally sound society in the world. A stay on the island republic of Rastafari would refresh the parts other holidays couldn’t reach: starting with the mind, moving on to the soul, finally overhauling the body. And, unlike other holidays, its effects would continue to be felt long after you’d gone, possibly forever. A visit would bring many surprises, dispel many misconceptions, open new horizons. But the biggest surprise would be that such a country ever existed at all.

Like the coconut palms and turquoise seas, the Rastaman symbolises the Caribbean image the world over. No other group of people in its melting pot of cultures comes as close. And no other group has had it as hard. Against all odds, the Rastafarian faith has grown from an obscure rural sect in 1930s Jamaica to become, along with reggae to which it is inextricably bound, the Caribbean’s most successful cultural export.

Rastafari has metamorphosed to the extent that it has become a truly global phenomenon with an appeal which crosses all boundaries. Rasta organisations and communities now exist in places as unlikely as Japan, Moscow, Sweden, Poland — even Tibet, I’ve been told.

An irony is that it is Rastafari’s eclectic nature which makes a real Rasta state so unlikely. Rastafari has no command structure. It is not a church. It is not really a religion in the conventional sense either, though the Bible is central to Rasta philosophy. There is no one doctrine or set of beliefs: some wear dreadlocks, some trim and cut their hair short; some are vegetarian, some aren’t; most smoke the herb, but some don’t; some are very anti-technology, walking barefoot, while others have websites; some believe white is the devil, while most embrace all races; some are polygamous, some are not; some believe Haile Selassie is Christ, some say he is God, some say Prince Emmanuel of Jamaica is God.

In the words of one Rastafarian: “It is not something you become, but an inborn concept from creation which can come to a person at any time in their lives. God is within everybody, and this is manifested in different degrees. Those most able to manifest this Godliness and have influence on others are prophets. His Imperial Majesty was supreme in this ability; he was the living light to help others to discover their own Godliness through Rastafari . . . Rastafari is a way of life expressing one’s righteousness through the teachings of His Imperial Majesty.”

This is just one view of Rastafarian living; other Rastas might have different interpretations. There are endless variations of Rastafarian attitudes and beliefs; this is manifested by assorted sects of Rastafarians which vary in orthodoxy. The largest and most liberalised is The Twelve Tribes of Israel. At the opposite end, the Bobo Dreads practise the purest form of Rastafarianism in African-style rural communes.

Common to them all is a lifestyle that promotes peace, unity and love of the Creator. Rastas assert that everyone, in fact, is a Rastaman deep down inside — it is up to the person to recognise his true identity. It is the heart that decides who is Rasta and who is not.

Most Rastafarians are of African descent, a small minority of whom remain anti-white, but there are many Caucasian and Asian Rastas, too. I was told of diehard white Rastas in Sweden and Amsterdam, “barefoot hard-core Biblical brothers deep in the faith”. For most Rastafarians all people are totally equal and bound together by one God — Jah. They practise what Haile Selassie preached:

That until there are no longer any first class and second class citizens of any nation; that until the colour of a man’s skin is of no more significance than the colour of his eyes; that until basic human rights are equally guaranteed to all without regard to race . . . until that day, the dreams of lasting peace, world citizenship and the rule of international morality will remain but a fleeting illusion, to be pursued but never attained.

Given the original, central belief of repatriation to Africa — the rightful home of the black man and the birth of all civilisation in Ethiopia — it may seem a paradox that Rastafari should appeal to non-Africans, particularly whites. The Rasta, however, will argue that we are all of the same seed, the direct descendants of Adam and Eve. Ethiopia is where we all come from. As one man told me: “If the Throne of David was in the North Pole I’d rally there.”

Repatriation to Africa was a catalyst for the early success of Rastafari, but it is no longer the burning issue it was — Haile Selassie told the Rastafarians to build Jamaica first, rather than focus on emigration. Since the advent of reggae music, people of all cultures have begun to adopt and practise aspects of Rastafari which are meaningful to them.

On a practical level, a Rastafarian homeland might well be a country which functioned in a state of amiable anarchy; but the core values of its disparate groups would ensure it was a land where a person’s beliefs were valued and respected, where the plants and animals were equal partners with man. It would have much to teach the world.

On Herb and Hair

Herbs

He causeth the grass to grow for cattle, and herb for the service of Man (Psalm 104:14)

Marijuana, ganja, the wisdom weed, the herb found growing on Solomon’s grave, is the Rastafarian’s holy sacrament; a communion wine, if you like, but with a kick no vintage can match — essential and central to their beliefs.

It is the vehicle which carries the Rastafarian closer to God, to the universe He created, and to an understanding of himself. When he takes the herb it empowers him with the heights of reasoning, liberating his mind from the shackles of earth. With the herb inside him the Rastaman is one with Jah, each new thought and idea a voice from the Almighty himself. And though he would wish it were not the case, the herb nevertheless symbolises his independence from the establishment, from Babylon which, of course, forbids its use.

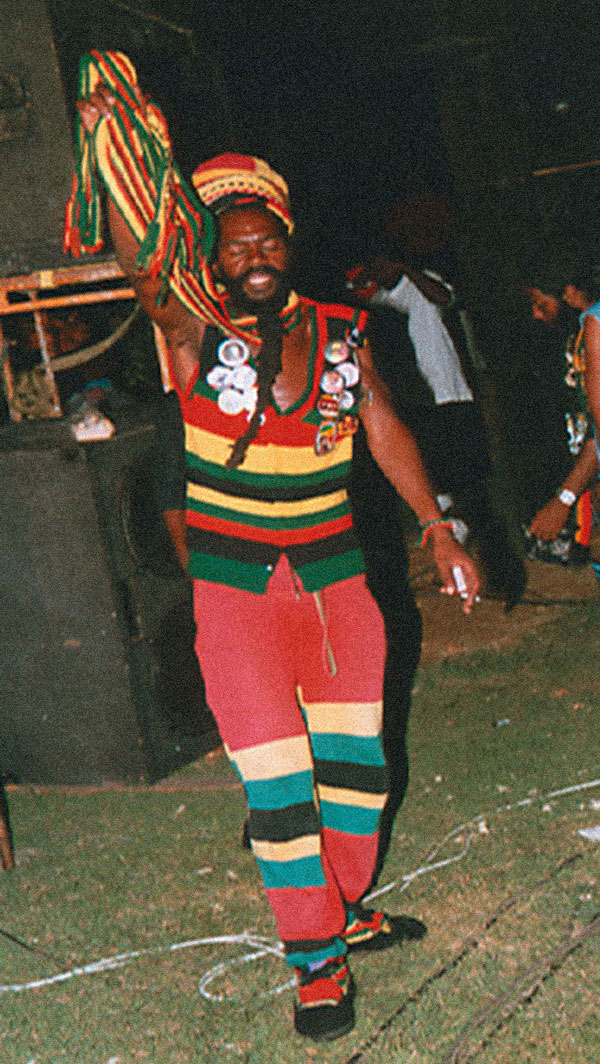

Any Rastaman you care to speak to will readily engage in passioned argument about the herb and its outlawed status, its spiritual and medicinal properties. I was instructed in this by one devout Rastafarian who cuts an imposing figure, reading the papers on the roadside in red, gold and green robes and colourful turban. He needed no second invitation to talk and took me for a walk into a wooded valley outside the city. Like many true Rastas his replies to questions on life are interpreted in a Biblical context. For him, there are no grey areas in the Bible; it is the word of God and irrefutable.

“When God created the world, he make bush, he make the herbs, the trees and forests, then the animals. Then he make . . . man. And he give man dominion over all things. All things,” he emphasises, arms spread wide, in a voice barely containing his wonder at the Almighty’s generosity. “Nobody can create a better miracle than what God has done. He gave man the herbs — to use.

“Why should a man be penalized and put in prison for God’s work? This man that is putting me in prison could not be made by God? I see him now as the same Roman soldier of Babylon. The soldier who crucified Christ. I see him following the concept of that . . . still!” He stabs the morning air with his finger.

He’s silent for a while, thinking, pondering; birdsong and insect noises fill the void.

“You know,” he says suddenly, “I sit down just now and I done smoke: a voice — and no-one else’s voice could that be but the Almighty — is telling me: ‘Hear now, see them brothers and them? Show them the way to travel. Give them that spiritual concept — love. See if you can get love from them. See if they can have love for one another. That you can bring that love together, as one, everywhere.'” His voice tails off, carried away on the breeze.

“So – how you come tell me marijuana is bad to smoke!? Look. A woman, a holy mother of our church, come and tell me she dream I bring marijuana root and the male marijuana in a cup of dry Vermouth, for . . . asthma. She say: ‘Oh God, me’s a woman who does suffer with asthma. Bring some weed for me.’ I can’t do that, I say, but if she can get it . . . (she does). God come and give that to her as a vision – in the sleep. Not a dream, eh. A vision. And the asthma cup? It heal her – one time! So — how marijuana bad?”

We reflect in silence. Parrots fly overhead, squawking loudly. My feet start getting bitten. The sun comes out behind a cloud illuminating the black and green turban. I ask why he wears his dreadlocks tucked inside it and he tells me he doesn’t like “having things crawling all over me face”. As a child he was given a hard time from 10 brothers and sisters for growing his dreadlocks: What yuh doin’ with that on yuh head?

“Look now,” he says. “Rastaman was oppressed so much. Every corner you turn you used to hear: Cut off that, nuh. Why don’t you trim and look nice? But — you are walking as Jesus Christ did. He walked with the same pattern, the same way the Rastafarian does right now. This is a spiritual concept, and the Rastaman don’t deal with nothin’ else. So – why it is that you can’t accept me into your society?”

Locks

They shall not make baldness upon their head, neither shall they shave off the corner of their beard, nor make any cuttings in their flesh. (Leviticus 21:5)

For devout Rastafarians, cutting the hair, or much of anything else, is expressly forbidden by the Bible. Jesus and his disciples are portrayed as “locksmen”.

A Rastafarian woman told me about her husband who was hospitalised for a brain tumour operation, a craniotomy. It entailed making a cut from one ear, over the top of his head to the other ear, and peeling back the skin of the face to get at the tumour behind the optic nerve. Despite the extreme delicacy of such an operation, the surgeon at a Houston cancer hospital respected his Rasta patient’s culture, performing surgery without removing the massive dreads. The surgeon was told it was a sin to cut his locks, and that the wages of sin was death.

Dreadlocks are the result of hair that is left completely natural; cleaned, but never combed. You can start them off by twisting the hair around your fingers. If you want neat, even ones, you should pull them apart every couple of days or so. Dreadlocks grow quickly because the hair that falls out becomes part of the dread instead of falling to the floor. Rastafarians often use natural ingredients like cocoa butter, aloe vera and “slime” from a type of cactus plant when washing and maintaining their locks.

Dreadlocks were so-called because of non-believers’ aversion to their appearance. Not all Rastafarians wear dreadlocks, which is why it is so difficult to put an accurate figure on Rastafarian numbers, anywhere. “Baldhead” or “clean-faced” Rastas look entirely conventional, a necessity for some of those holding down professional occupations. Youthful Rastas favour “ragamuffin” style, cut short with a small “ras” on top, often tucked into a cap.

History

Jah Live!

April 21, 1966, was a day like no other for the Rastafarian in Jamaica. It was a day which would be forever marked by the visit to their island of their God, His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie. And it was a day His Majesty probably never forgot, either.

Nothing he had heard about a Jamaican cult worshipping him as the Living God could have prepared Haile Selassie, a devout Christian, for the sight filling his airplane window. A crowd of 100,000 had turned up to meet him, most of them on a holy pilgrimage. The airport tarmac was awash with an endless sea of dreadlocked, white-robed Rastas chanting “Hosanna to the Son of David”.

Thousands of curious non-believing poor Jamaicans had also taken the day off, curious to see this “black messiah” and not taking a chance on the possibility of deliverance. Haile Selassie couldn’t leave his plane, even if he had wanted to, which he didn’t. It was only after an address to the crowd for calm by a respected Rastafarian Elder that His Majesty was able to reach the car for his journey to the capital.

Thirty-six years before his visit, Haile Selassie had become, by default and quite unknown to him, the Living God of Abraham and Isaac to a small Jamaican cult called Rastafarians. The pictures on the front page of the Daily Gleaner on November 11, 1930, held special significance for the Rastas. They showed the coronation in Ethiopia of Ras Tafari Makonnen as “His Imperial Majesty Emperor Haile Selassie I, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Conquering Lion of The Tribe of Judah, Elect of God and Light of the World”.

Rastafarians, like many people of African descent in Jamaica and the United States, followed the teachings of Marcus Garvey, founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association in the United States. To them, Garvey was a prophet who had foretold: “Look to Africa when a black king shall be crowned, for the day of deliverance is near.”

Garvey preached black nationalism and racial pride: “Africa for the Africans — at home and abroad.” His was the Biblical view, that “every nation must come to rest beneath their own vine and fig tree”. He believed that without the liberation of the African continent from colonialism there would be no uplifting of black people. Garvey sought to establish a black state in Africa where Africans in the West would be transported, even starting a shipping line to do it. The Black Star Line failed, but his message did not.

For the Rastas, the Biblical titles and newsreel footage of Haile Selassie’s extravagant coronation had a profound impact. They confirmed to many that Marcus Garvey’s reportedly prophetic words, foretelling the coming of a “mighty king” who would arise in the east to bring justice to the oppressed, had been fulfilled. Followers consulted their Bibles and found in Revelations various texts confirming that this was, indeed, the king of whom Garvey spoke.

To traditional followers of Garvey, Haile Selassie was a hero of black nationalism. But to the Rastafarians he was the Living God, a doctrine which had been developed independently by several Rasta elders, among them Leonard P. Howell. Garvey disagreed with their view, regarding the Rastafarians as fanatics. And he had little time for Haile Selassie, noting that slavery still existed in Ethiopia.

Elders in the fledgling Rastafarian movement disagreed about many things, but all were united that Haile Selassie was divine. The other matter which united them was immediate emigration to Ethiopia: “Let my people go”.

This demand remained unmet by the authorities. In 1940 Leonard P. Howell purchased an abandoned estate called The Pinnacle which he ran as an independent Rastafarian mini-state in the style of an African chief. A year later the police were arresting many of the 1,600-strong community for growing ganja — their main cash crop – and for violence. Howell, who had preached violence and hatred of the white race, was among them. But he returned to The Pinnacle from prison in 1943 to continue where he had left off, preaching his own divinity and, eventually, becoming Kingston’s main supplier of marijuana. In 1954 his state-within-a-state was finally broken up by the police.

Rural followers of Howell and other Elders began migrating to the slums of Kingston where the cult of Rastafari and its message of protest and spiritual salvation grew steadily among the ghettoes. By 1960 there were 10-15,000 Rastafari brethren living in Kingston. There was also more violence. Some Rastas had rejected the non-violent teachings of authentic elders and become desperate at the government’s continued refusal to meet their demands. There were gun battles between British troops and Rastas, the latter suddenly gaining worldwide publicity for all the wrong reasons.

In 1960 a report on the Rastafari movement in Kingston by the University College of the West Indies urged Prime Minister Norman Manley to make the problems of the brethren a priority for treatment, remarking that “the movement was large and in a state of great unrest”. The report concluded that Rastafarians were stereotyped by society as bearded layabouts who stole, smoked ganja and were liable to sudden violence. The authors warned that if they continued to be wrongly treated as such, more would become extremist. What had struck them most in their investigations was the Rastafarians’ deeply religious nature; how meetings began and ended with hymns and psalms, and were punctuated by prayer. “A movement which is so deeply religious need not become a menace to society,” they advised.

Negative attitudes prevailed, though: criminals and opportunists had infiltrated the burgeoning Rastafarian movement where the supply and consumption of ganja was accelerating far beyond Rasta circles. Dreadlocks were an easy disguise with which to obtain information about marijuana. The media fed the myth of Rastas as crazy, gun-toting drug dealers.

In the 1970s, reggae emerged as a force in world music, thanks to Bob Marley. This turned the fortunes of the Rastaman around. Bob Marley did more than anyone to spread the positive message of Rastafari. His inspirational songs of love, racial harmony and pride brought new converts to the movement from around the globe. Seventeen years after his death, his legacy of “one love” is finding a home among a new generation — of all races.

It’s hard to put a figure on Rasta numbers, but ten years ago they were estimated at 700,000. Nowadays, you only need to surf the Net to see how far Rastafari has come. There are Swedish websites dedicated to Rastafari, French ones, Dutch, Danish, Norwegian, Russian and Japanese.

His Majesty would need a mighty airport next time around.

Profile: Destiny’s Rasta Child

Keith ‘Destiny’ Waldron is a reggae musician. When he’s not writing songs and singing them, he’s selling them. But hustling his cassettes around town takes up far more time than he would like; it’s hot, hard work requiring endless reserves of charm and chat. What he would like, more than anything, is that the radio stations and record stores would do the job for him.

He wants a recording contract, but until that happens Higher Meditation, his 10-track cassette of roots reggae songs, will continue to rattle around in his rucksack, seeping slowly into the public consciousness through a slog of countless sales pitches and an unshakeable belief in his music and his god.

Destiny needs no encouragement to talk about his music; conversation invariably returns to his ambition for it, liberally illustrated by verse from any one of his songs. These are inextricably linked to his faith, and issues which concern all Rastafarians: Praise The Lord Thy God, or Mr Boss and Oppressor, or Boys in Blue, his newest recording about the law’s attitudes to his holy sacrament of marijuana.

Bob Marley, poverty and black rights, and an upbringing as a Spiritual Baptist, ensured Destiny was ripe for Rastafari while still at school. “There was always a spiritual and musical culture in the house,” he explains. “I come from a line of Spiritual Baptists. My mother did a lot of singing and my father taught dancing. I was baptised and we went to church and did confirmation and read the Bible from a very early age.

“I came from a rural background and supported the rights of the poor whenever I could. I wanted to join the marches at the time of the Black Power Movement in Trinidad, but my mother wouldn’t let me because I was ‘only a little guy’. I began reading books on Rastafari and His Majesty Haile Selassie I, listening to Bob Marley and what he was saying, and learning to play the guitar. Later, when Bob was sick, I remember sleeping with a book on my bed, and a pen; writing, writing, always writing.

“Rastafari brought me to understand myself a little more. To know my direction. To know exactly where I was going. Now I know where I came from. It changed me, and it changed people around me in some way, too.

“Rastafari is not just the hairstyle,” (he grins, shaking his dreads for effect) “it’s the way a man thinks. People are taught to judge on appearances, but it’s what’s inside the clothes that counts. Rasta is in the heart. If I reject you, I restrict myself. If you come to me with love, then I will have to deal with you with love.”

But the lack of love towards Rastafarians is a burden he knows will continue: that most are unlikely to win the job over the man with the short haircut; that their ways will always be subject to misconceptions and prejudice:

“These things are normal for a Rastaman. No one likes it. No-one wants to be hassled. A man’s culture should be respected. Who is man to come criticise us? Jah made the herbs on this planet. Who is man to come and eliminate it? I build higher heights of I-Iration, and I smoke Jah Herb for higher dedication. This is the reason.

“I would like to say that I give thanks and praise unto the most high God, Jah Rastafari Selassie I the First. I want to see the people accepting Rastafari. I want to know people are listening to my music. Yes, I would love to go to Africa. Any day. Any time. Right now!”

Rasta Romance

Sista Irie hosts a reggae radio show in Austin, Texas, called the Conscious Party on KAZI 88.7 FM. Her passion for reggae and Rastafari has travelled the airwaves for the last eight years, during which time she has been taking its message into federal prisons in Texas and Arkansas, through music and literature.

Sista Irie was once Beverly Shaw. Then she went to Jamaica and met Ricky, a Rastafarian, and nothing was ever the same again. “I started travelling to Jamaica in the late 70s, to Negril, before it became a big tourist area. For years I used to watch Ricky and other fisherman go out to sea in their dug-out canoes, returning with boatloads of magnificent sea creatures. In 1986, Hurricane Gilbert hit the island and blew Ricky’s house down. Humble as it was, he lost everything he had accumulated over the years. At the time I was staying at his best friend’s house, and Ricky would come over to shower and cook yard-style. We became better and better friends and, one night, we saw each other at a reggae concert, began dancing, and have been together ever since.”

They married in 1990 because the US Government would not allow him in as a visitor. They had not intended to marry, which is common among Rastafarians, but it was the only way to be together. When not broadcasting, Sista Irie works as a buyer for a chain of outdoor adventure/travel stores, while Ricky is a manager at a local chain of bakery and delicatessen outlets.

“Both of us live a Rastafarian lifestyle and we still go dancing at the local reggae club every weekend. We have re-built a little house in Negril called the Love Nest, named after our original shed which was left over from the hurricane. We hope to move back to Jamaica after we have put some money away.

“Ricky and I both believe it was divine inspiration that brought us together. We both believe strongly that racism is the root of most evil. We feel our love for each other is good for others to see. I have been blessed by this marriage . . . to have such a gentle and loving Rasta husband who has taught me more about life from his many years at sea than I could ever have learned in church or college.

“Rastafari, as expressed through reggae music, has been the foundation of our life together. Reggae music has changed people’s ways of looking at life. The music is a message, and when people hear it they know it is good and righteous. Those who abhor racism are particularly drawn to it, which explains why so many different races and cultures adhere to this belief system, people from all walks of life all over the world. This is the true beauty of Rasta and Reggae.”

MUSIC

Reggae: The Hymns of a New Religion

It’s safe to say that without the Rastafarian religion, reggae music would never have become the international cultural phenomenon it is today.

It’s equally safe to say that without reggae music, the Rastafarian religion wouldn’t have progressed from a tiny, loosely-knit Jamaican cult, viewed with a mixture of hostility and suspicion by virtually everyone who wasn’t in it, to a movement of considerable global significance and substance.

Reggae and Rasta. Rasta and Reggae.

Throughout history, virtually all religions have had their hymns and their chants. Worship and music have gone together like Astaire and Rogers, Ramadhin and Valentine, ackee and saltfish. But never have the two been so inexorably linked, both in public perception and reality, as reggae, with its heartbeat drum and bass rhythms, and the Rastafarian religion, with its heartfelt, fundamental philosophies.

And never has a religion used music to carry its message to so many people around the world. If you’ve listened to more than half a dozen reggae songs, you’ve learned, through them, something about Rasta. It’s religion you can dance to, and that’s all part and parcel of reggae’s seductive appeal. But when the dancing’s done, reggae also has the power to make listeners think. And, in many cases, to think again about a lot of things they’ve taken for granted in the past.

Reggae has never been a music that paid much attention to facts and statistics, and there’s no way to pin down any hard and fast figures about what proportion of reggae musicians are actually members of the Rastafarian religion. But after following the music for more than a quarter-century, I’d estimate that at least 80% of all reggae musicians are either serious followers of Rasta or have been strongly influenced by the religion.

The most famous reggae artist, of course, is Bob Marley.

I use the present tense for the simple reason that Robert Nesta Marley has become immeasurably bigger since he died than he ever was when he was alive . . . and he was a major-league international superstar then.

Marley was a musician of global stature when he died in 1981. Since then, he’s become much, much more than simply a charismatic singer-songwriter. In death, Marley’s reputation has reached almost mythic proportions. His dreadlocked image has undoubtedly adorned more T-shirts — arguably the ultimate international yardstick of recognition — than any other single personality. His songs of freedom, hope, love and liberation – sprinkled with a healthy dose of anger and rebellion — have become international anthems.

Somewhere along the way, Marley has also become the single most identifiable embodiment of Rastafarianism, better-known and better understood by far than Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, the man he himself revered as Rasta’s living God – “Jah Live”, Bob sang, in one of his most spontaneous and memorable compositions, when reports of Selassie’s death first reached Jamaica.

Chances are that Bob Marley, a modest genius, would have felt more than a little uncomfortable with the adulation and almost god-like status that have come his way posthumously. He would also, without question, have been delighted that his earthly achievements have played such a major role in Rasta’s global emergence.

And, make no mistake, the formidable combination of Rasta and Reggae has become a global happening. It’s also, more than 30 years after ska and rock steady evolved into reggae and started to go international, a phenomenon that continues to spread, continues to penetrate new areas.

Listen to musicologist Roger Steffens, reggae’s most respected historian: “I’m fascinated by the ability of so many disparate cultures to absorb the basic sound and vocabulary of rasta reggae, yet turn them into something else again. In Nigeria, for example, where reggae is enormously popular, an artist calling himself Ras Kimono recorded his own interpretation of Rastaman Chant, while his countryman Majek Fashek also makes frequent mention of Ras Tafari. But for them Selassie is not God, as Jamaican Rastafarians believe, but rather a metaphor for the empowerment of black people, a symbol of opposition to the System, an almost neutral figure around which to rally.

“In Poland, in the shipyard of Gdansk in the 80s, thousands of Poles wearing red, gold and green would gather to hear all-day reggae concerts, during which the rallying cry of Rastafari was often invoked, inspiring revolt.

“And I’ll never forget the Reggae Sunsplash of 1984, when Zound System from Japan were playing. They brought with them a gigantic log drum, suspended horizontally six feet above the stage, and beat it in a 13th-century Asian rhythm that was identical to the heartbeat underpinning of reggae, while in the corner of the stage, two Japanese beauties clad in colourful traditional kimonos screamed ‘Lasta-fal-I! Jah rib!’

“To me, reggae’s most powerful exponent, to this day, is Bob, and there’s no doubt his work has penetrated to the very heart of Babylon. Witness this quote from the 100th anniversary edition of the New York Times Magazine, when each of their critics was asked to choose one work of art from this century that would last a hundred years into the future. John Pareles, their ever-astute chief pop music critic, chose the original Wailers’ last album together, Burnin’, and wrote: ‘In 2096, when the former third world has over-run and colonised the former superpowers, Bob Marley will be commemorated as a saint’.

“And Jack Healey, the head of Amnesty International, is on record as saying: ‘Everywhere I go in the world today, Bob Marley is recognised as the symbol of freedom.'”

Even as Marley’s influence — and the influence of Rasta-inspired reggae — continues to spread, a talented new generation of singers and songwriters is taking care of Bob’s unfinished business.

Classic roots performers like Culture and Dennis Brown are still touring, recording and attracting a new generation of fans, but much of today’s reggae is dramatically different, rhythmically, from the sounds that ruled when Marley was reggae’s undisputed living king. The rhythms may be different, but the Rastafarian religion continues to have a huge influence on the music. A classic example of this is Buju Banton, who burst on the deejay scene in the early Nineties with the roughest voice in the business and some of the crudest, nastiest lyrics. Over the past two or three years, with Rasta playing a bigger role in his life and his thinking, Banton has mellowed drastically, and the evocative, positive lyrics in his two most recent CDs are perhaps the strongest to emerge on the reggae scene since Bob left us.

What’s next for Rasta-influenced reggae? You’d need a crystal ball to answer that question, but one thing’s for sure: the music that gave the world Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Jimmy Cliff, Toots Hibbert, Joseph Hill, Dennis Brown, Beres Hammond, Bunny Wailer, Lucky Dube, Alpha Blondy, Gregory Issacs and literally hundreds of other superb artists will continue to entertain and enlighten millions of people around the world for decades to come.

Garry Steckles