For some Trinidadians, Andy Narell represents something of a dilemma.

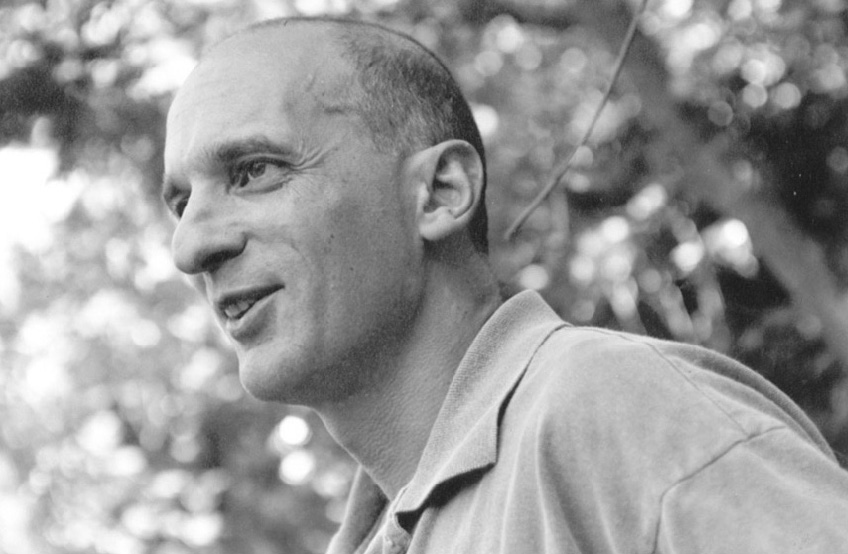

The slim, sad-eyed musician is the most widely recorded steelpan player in the world, with 11 CDs to his credit, as well as numerous movie, TV and commercial soundtracks. He’s made music with Taj Mahal, Chucho Valdes, Marcus Miller, Aretha Franklin, Pete Escovedo, the Pointer Sisters and Patti LaBelle, among many others. And for nearly 15 years he’s been a close friend and collaborator of Trinidad’s calypso idol David Rudder; indeed, he (together with local pan ace Robbie Greenidge) performed on the Savannah stage with Rudder in 1987, the year after the young calypsonian electrified the nation by winning all three major calypso titles — Young King, Calypso Monarch and Road March.

In short, Narell can beat pan with the very best of them. And therein (for some, at least) lies the dilemma: Narell is not just white, he is American. Not a local boy, by any stretch of the imagination. Trinis, it must be said, can be very possessive of their national instrument, and anything that pertains to it.

Which is why a letter on Andy Narell’s desk, one sunny Friday last September, seemed almost to be radiating an urgent, orange aura. It’s not exactly illegal for a non-Trinidadian to compose and arrange a Panorama tune; but it had never happened yet. The letter on Narell’s desk was proposing to change all that.

Panorama, for the uninitiated, is the zenith of steelband music in Trinidad, the land where this music was born. In the years since the steel pan was invented (circa 1940), it has become politics, religion, class-struggle, and a sweet fire in the soul, all rolled into one. Every year, just before Carnival, the entire country locks into a wildly popular national pan competition: Panorama. The top steel bands swell to 100 or more players beating close to 300 pans, and talented composer-arrangers like Len “Boogsie” Sharpe, Jit Samaroo and Ray Holman create ten-minute musical extravaganzas for the occasion. Only one band wins.

The thundering, percussive, polyrhythmic roar of these huge bands, with their pounding bass pans and jazzy melodies moving from section to section, is so exciting it can make you weak in the knees. This is competition at its very fiercest.

No steelband has ever placed its fate in the hands of a foreign arranger; but Narell’s radioactive letter was from Junior Regrello, leader of a top band called the Hydro Agri Skiffle Bunch. It was an invitation for the American to come to Trinidad and compose/arrange an original tune for the band to play in Panorama 1999.

It was an unbelievable honour. It was an unprecedented opportunity. It was an irresistible challenge. So why was Narell dragging his feet?

“Some of the factors are . . . well, for one thing, the whole culture of . . . winning,” explains Narell. “Panorama is so tied to Carnival that you don’t dare come in with a tempo that’s a few shades under someone else’s tempo or you’re gonna get knocked out of the Savannah.

“Also,” he adds, “it’s become almost the antithesis of uniqueness and diversity. In the old days, bands like Desperadoes and Invaders and North Stars and Cavaliers and All Stars wanted to sound as different as possible. It would show in the arrangements and the sounds of the pans, and everything. The obsession with winning Panorama has caused everyone to sound more and more alike.”

So Narell was working on a letter to Regrello. It read, in part: “If you don’t think that most of the bands play too fast and too loud, you shouldn’t hire me, because I do — I would rather come in tenth and hear that everybody’s arguing over whether it was the most beautiful tune in the Panorama or a bunch of s–––, than come in third and hear everybody say that Andy Narell finally came down here to do a tune and he had nothing to say.”

Andy Narell has an international reputation. His hot new CD, Behind the Bridge, features a great playlist of tunes from Cuba, Brazil and Trinidad, and showcases the panman at the top of his form. What’s more, Narell deserves an enormous share of the credit for popularising Caribbean music in North America. Aside from his own gigs (where he always cites sources and roots for his music), radio interviews and teaching workshops, he paid out of pocket to bring an entire steel orchestra (Our Boys) to the San Francisco Bay Area, and put them in the studio. He was also responsible for arranging David Rudder’s first gigs at the Great American Music Hall.

Narell made his first contact with the steelpan almost as early as your average Trinidadian kid. He was only seven years old in 1961, when his father, Murray Narell, a social worker on New York’s lower east side, started one of the first steelband programmes in the US. Pans were quite new at the time, having emerged as a melodic instrument in Trinidad only about 20 years earlier. Murray Narell travelled to Trinidad several times, meeting legendary pan tuners like Ellie Mannette and Rudolph Charles, taking notes and writing it all down.

“My father brought a few pans home,” Narell recalls, “and we started playing as a family. I was eight years old by then. We did several hundred gigs between 1962 and when I was 15, which was when we left New York. We played for weddings and bar mitzvahs, huge benefits at Madison Square Garden, even the Ed Sullivan TV show.” Soon the younger Narell began visiting Trinidad too. “We went down to play the National Music Festival in 1966,” he notes. “We played as guest artists at Queen’s Hall. I was only 12, but I went to all the panyards, I met Tony Williams and heard North Stars rehearsing, I went to the Invaders’ yard and met Ellie Mannette . . . so I’ve always had a sense of where all this comes from.”

Hey, Lox Man!” yells Narell, late in 1998, as his door opens to reveal Trinidad superstar David Rudder, suitcase in hand. (Narell’s nickname refers both to Rudder’s handsome dreadlocks and his fondness for smoked salmon.) Rudder is in the San Francisco Bay Area to begin rehearsals for a major steelpan-and-calypso concert with Narell.

It’s no surprise that Rudder and Narell are pals. Both are cross-cultural phenomena: Narell knows more about Caribbean music and culture than four ethnomusicologists, while Rudder, a keen student of American rock, blues and R&B, has brought a variety of international influences to bear on his calypso, reinventing the genre for a new generation.

Their relationship has been dogged by controversy almost from the start. Back in 1987, when Narell played behind Rudder on the Savannah stage, resentful nationalists thought the calypsonian was “fas’ and out of place” to bring a foreigner to such hallowed ground. “Some people did say ‘Boy, yuh bring Andy Narell to play for you, why yuh didn’t bring a Trini?’” Rudder recalls. “But that’s just talk. Trinidad is a land that thrives on controversy; even if there’s none at Carnival time, somebody will make some.”

Rudder himself had no problem with his friend’s nationality. “I always believe that pan is not ours,” he says. “We got the gift of the creation, but when you get a gift you don’t hide it, you have to give it.” Over the last ten years he’s worked quite a few gigs with Narell. It’s a different sound from Charlie’s Roots (his hometown band), explains Rudder — who is very particular about who backs him in live performances. “As an artist you look for different interpretations of your music. But I don’t want to play with people who can’t understand what I say.”

“If there’s a unique qualification my band and I have,” adds Narell, “it’s respect for the music. There are a lot of good musicians who have an attitude about Caribbean music, that it’s simpler and less involved than the music they normally play. We have enough respect for that music to take it very seriously.”

Despite his achievements as a pan player of international renown, Narell does not always find it easy to get his message across. The music press, he finds, approaches the rich field of “world music” with a certain superficiality.

“It’s always frustrating,” he says, “to see pop and jazz artists who just lay their thing on top of tracks played by musicians from other countries, and haven’t taken the time to learn very much about that music, getting huge amounts of press for ‘interacting with the world music scene.’ I do this! I play this music. I go down to these countries and they accept me as one of their own. In Trinidad people know that I can play Trinidadian music like a Trinidadian. They know that when I’m out on a gig and talking about where the pan came from and the culture of calypso in Trinidad, I’ll get it right.

“The more you go around the world and look at music and try to understand it, the more there is. Nearly every culture has something about its music that will give you a window into the soul of its people.

“You could spend your whole lifetime trying to understand calypso. Not just the groove, or the beat behind it, but the whole art form, its function in society, its development as an art that encompasses the music element, the performance element, the political element, the social commentary, the humour, the smut, everything! And then we start connecting the music, what happened on the instrumental side, what’s happened with the pan, how this incredible invention happened in Trinidad. . . I just try to keep learning!”

The steel-and-calypso concert in the Bay Area is underway. Narell is playing his Quaduets, a new kind of pan he’s been working on with master tuner Ellie Mannette. It’s a four-drum set: two double seconds extended on each side by out-rider pans that provide eight additional notes at the bottom of the double seconds’ normal range. The pans resonate with beautiful, bell-like tones, Mannette’s trademark. Narell has one of the only sets in existence.

Narell hardly touches the pans when he plays; his arms and hands seem totally relaxed, letting the sticks fall onto the steel, not driving them. He knows exactly where the sweet spots on the notes lie, and can stroke the music out, no need to beat up the pans. His neck bends, his shoulders dance, as he draws music from the taut-stretched steel.

The dance floor is jammed with whirling, jumping, gyrating, wining bodies, and even a few bottle-and-spoon players. This is a familiar scene in Trinidad, but it’s the first time that a Bay Area audience has really caught the steelband spirit. Narell’s face is something to see. He’s home.

Maybe that’s when he made his decision. In any case, it was while he was packing away his pans after the show that he announced — his voice almost a whisper — “I’m gonna do it. I’m gonna do the Panorama tune.”

The Skiffle Bunch had agreed to all his conditions; but it was about more than that. Sure, Narell would be walking into the lion’s den, but this stuff was in his blood. On some level he’s held dual musical citizenship all these years. Now he had to find out if he could walk the walk, play de chorus.

“At some point,” Narell mused, “ you either gotta put up or shut up. You’ve got to go in and try to do it. If you have an opinion about how they should be doin’ this instead of doin’ that, shut up and go do it! Ever since I went down to Trinidad and played in the bands, I’ve dreamt that I’d come back someday and do my own tune.”

1999 was the year Narell’s dream came true; and Trinidad’s Panorama will never be the same. On the eve of the millenium, Andy Narell created steelband history.

By the week leading up to the all-important Panorama Preliminaries in late January, Narell was virtually living at the Skiffle Bunch panyard on Coffee Street in San Fernando.

And he had acquired a nickname: The Beast. Not because he was mean; quite the opposite. But by now, infected by the competitive spirit of Panorama, Narell was pushing the band hard.

“I do feel like I’m in the crosshairs,” he added. “Everyone’s crosshairs. Jit, Boogsie, Bradley, Philmore, alla dem. They can’t lose to me, it would be a disgrace. So I’m starting out to win the South Prelims, and then we’ll see.”

One of the secrets of Carnival that many tourists never catch on to is that Panorama doesn’t happen in the Grand Stand, or even in the North Stand. It happens in the yards and in the Drag (the road leading to the competition stage in the Savannah). Here in the Skiffle Bunch panyard, with Narell’s help, the band was finding the sweet spots in the rhythm and in the arrangement, learning where it was possible to give the music a tiny push to make it explode. Practice makes this possible. The better you know where your stick needs to land, and when, the better you can fine-tune the precise time and place where it makes contact with the steel. You can make the tune swing.

At the same time, the winds of public opinion seemed to be shifting into Narell’s favour. Early in February, Keith Smith, Editor-at-Large for the Trinidad Express, wrote: “Narell is such a nice man and so patently on our side that I don’t see how, after all these years, we could have avoided embracing him.”

The night before the Prelims, Narell gathered the band under a drizzly sky and delivered a short speech that had many band members in tears. Among other things he said:

I came down here with a purpose. First of all, I came down here to give something to the people of this country. This piece is a gift to the people of Trinidad. This is a country where I want to feel like I belong, and I’ve wanted that for a long time.

I really never intended to come down here and win Panorama. I didn’t think that would be possible. But when I listen to what you guys have done, I realize that we can win this Panorama. I can’t say what the judges will do, but we have a chance to do something remarkable. This is something special. I love this band. I’m as proud of this as of anything I’ve ever been a part of in my life.

Skiffle Bunch drew the last slot for the South Zonal Prelims. By the time the pans rolled on stage at Skinner Park it was 4.30 a.m. and the band had lost a lot of energy. Still, it played well enough to cop second place and advance to the semis at the Big Yard in Port of Spain.

And sure enough, playing well in the semis, the Skiffles did made the finals — but this time, going up against bands like Desperadoes and Phase II, it squeaked through with the lowest qualifying score in the pack. “Brilliant,” said the pan experts. “Unique. It jazz for so — but it not Panorama.”

Narell was so disappointed he got sick, but two days later he was back in the yard, looking shaky but drilling the band as hard as ever.

“Actually,” he admitted, “this is exactly what I expected to happen when I first wrote the piece, but the band was playing so well that I got lured into thinking we could win. I forgot that the judges were judging me, and this piece of avant-garde music. I’m really proud of the band. Almost everyone else was slamming their pans, and these guys had the discipline to dig in and play music. But we still came last. And no matter how well we play in the finals we’re probably going to come last again.”

But he was wrong. One week later, playing in the finals (and pushing the tune much faster than he had ever anticipated) Narell and the Skiffles came eighth out of 12 — beating Invaders, Starlift, Solo Pan Knights and Fonclaire (which was disqualified). Despers won, as everyone expected.

Most important, just as Narell had hoped, a dialogue opened on just what limitations, if any, should be placed on Panorama music. From on-air TV commentators to newspaper pan pundits, Narell’s challenge was being taken very seriously.

“By next year,” pointed out a Trinidadian friend as the Skiffles loaded their pans back onto the flatbed trucks, “people will be loving this tune, and plenty arrangers will be stealing pieces of it.”

“Well you know,” said Narell, “I came down here to stir things up. And ultimately that’s exactly what I did.”

Would he consider coming again next year? Arranging for another band?

“I don’t see how I could resist,” he grinned. “Coming eighth stung — for about four seconds. Then I felt great! It means I can work. Hey, next year I might even try arranging for two bands!”