Most people who know even a bit about Caribbean literature will have heard of Aimé Césaire, the poet-politician from Martinique. That French- (and Creole-) speaking island has also produced some other well-known writers over the last few decades—Edouard Glissant, Raphaël Constant and Patrick Chamoiseau, whose epic novel Texaco won the coveted Prix Goncourt in Paris in 1992. This small Caribbean outpost of the French Republic has, in fact, a flourishing literary scene that (much to the chagrin of the pro-independence intelligentsia) is probably largely due to enormous subsidies from Paris.

But much less known is the case of René Maran, born 120 years ago, on November 5, 1882, who was the first black writer to win the Prix Goncourt in 1921—seven decades before Chamoiseau.

Maran was technically Martiniquan, even though he was born on a boat bearing his mother and father there from French Guiana, their homeland. Three days later, the vessel arrived at Fort-de-France and the baby was duly registered as born in Martinique. There he stayed for seven years until his father, a civil servant, was transferred to another corner of the French colonial empire, Gabon, in West Africa. The young René accompanied his parents and two years later was sent to school in Bordeaux.

Like his father, Maran thought of himself as a Frenchman first and foremost, an attitude reinforced by his education in France. He also developed an interest in literature and at the age of 27, having studied law, published his first poetry. He then returned to Gabon and joined his father as a fonctionnaire in his own right.

Yet Maran’s patriotism could not blind him to the barbarism of colonial life in Africa. While he worked as a dutiful civil servant, he collected impressions and stories of exploitation and cruelty. He saw how local people were taxed, bullied and abused by French officialdom and how indigenous African culture was derided in the name of the “civilising mission.” These experiences were to form the subject matter of a novel that he worked on for nine years.

This book was the story of an African village, told by its chief Batouala. It dealt with the gradual and relentless destruction of the community by colonial rule as well as with the poetically celebrated beauty of the African landscape. Most importantly, its preface contained a vehement critique of the colonial system, outlining the cruelty, incompetence and near-epidemic alcoholism of the French authorities in an extraordinary outburst of anger.

When the Parisian publishers Albin Michel released Batouala: veritable roman nègre in 1921, neither they nor the author—still living in Gabon—could have predicted the response. First, there was outrage that a colonial functionary could have written such a damning indictment of French policy in Africa. One member of Parliament apparently asked the Minister of Colonies what punishment he intended to impose against the author. Columnists and critics in right-wing newspapers were characteristically indignant. Fury among conservative and pro-colonial circles was matched, however, by approval from more liberal commentators, who saw Batouala as an authentic expression of African reality.

Maran, oblivious to the storm in distant Paris, must have been astonished when he learned one day in late 1921 that his novel had won the Prix Goncourt—just two years after Marcel Proust had taken the prize. Realising that his days as a civil servant were numbered, he moved to Paris, hoping to write for a living, but never again found real literary success. Batouala was translated into 16 languages, yet for the next 40 years until his death in 1960 Maran struggled for recognition. But with his first novel he had struck a powerful blow against the system he had previously served so diligently and in the process had become what the great Senegalese writer Léopold Sédar Senghor described as a precursor of négritude.

The term négritude is commonly associated with Senghor and also with his friend and contemporary Aimé Césaire. It means, in essence, a sense of pride in being black and—in cultural terms—a belief that Africa’s traditions and artistic expressions are as valuable and significant as those of Europe and the West. Formulated by black students and intellectuals in the cafés of Paris, it is a militant doctrine, born out of the sort of experience that Maran described in his novel. It is also a doctrine that resonated in the Caribbean of the 1940s and 1950s when the old colonial order was coming to an end.

If Maran spent little time in Martinique, Césaire by contrast has devoted most of his long and varied life to his native island. Probably more than anybody else, Césaire was responsible for the arrangement reached in 1946 whereby Martinique (as well as Guadeloupe and French Guiana) became overseas departments of France, with substantial autonomy and full rights of citizenship. He was a député in the French parliament for many years and mayor of Fort-de-France for even longer before retiring from politics in 1993.

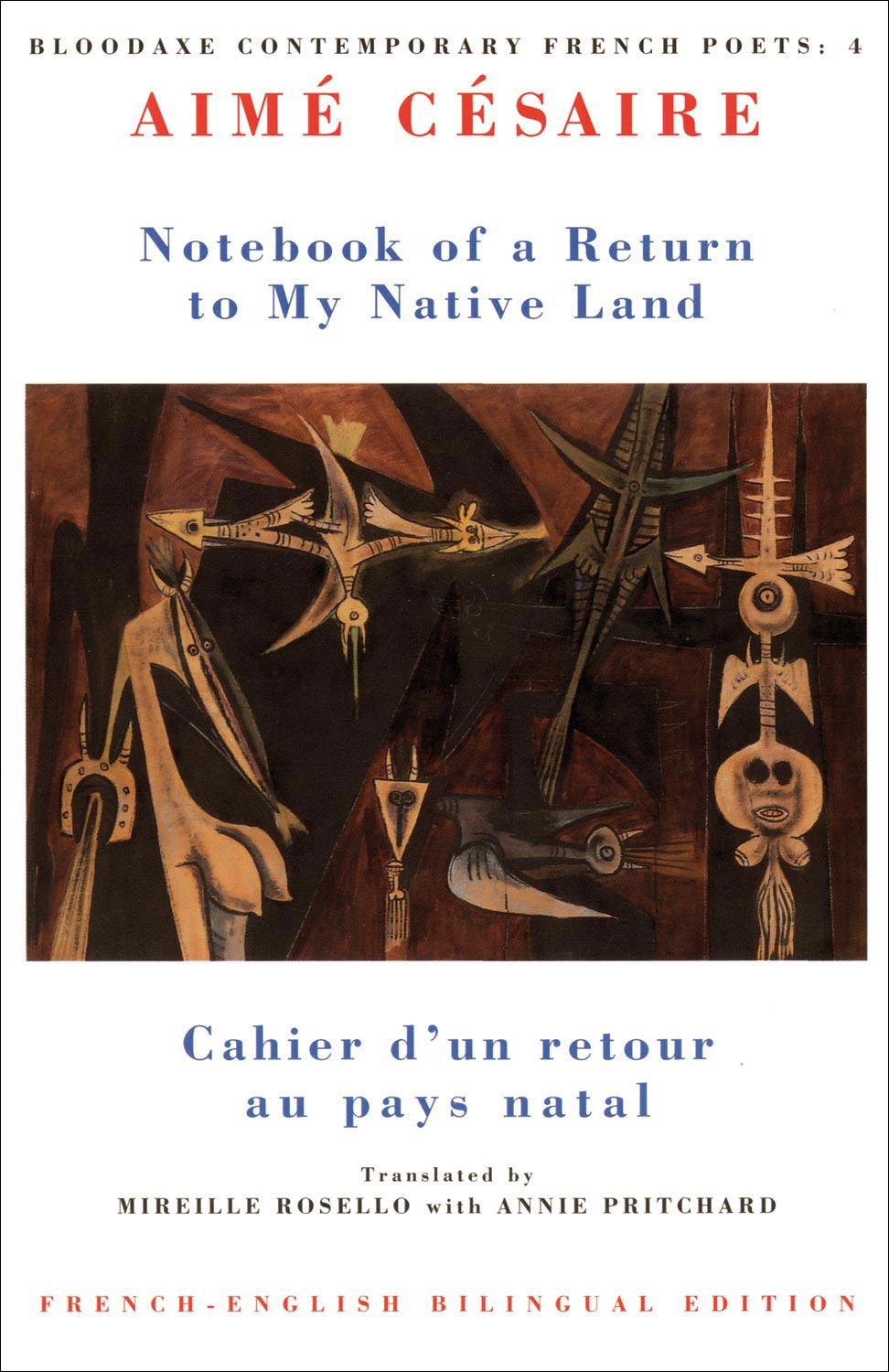

Césaire dominated political life in Martinique for almost half a century, yet he is best known outside the island for his acclaimed masterpiece of negritude, Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to My Native Land). First and partially published in an obscure avant-garde journal, this epic poem appeared in its own right and in its final form 60 years ago, in late 1947.

Césaire’s seminal work is in no sense an easy read. In extravagantly surrealistic imagery, it develops the contrast between a moribund Western culture and the vibrant and revolutionary aesthetic of negritude, which seeks to express itself through the violence of language:

my negritude is not a stone

nor a deafness flung against the clamour of the day

my negritude is not a white speck of dead water

on the dead eye of the earth

my negritude is neither tower nor cathedralit plunges into the red flesh of the soil

it plunges into the blazing flesh of the sky

my negritude riddles with holes

the dense affliction of its worthy patience.

The Cahier was a landmark in modern poetry, challenging conventions of rhyming and subject matter and suggesting a radical mix of surrealism and prototype Black Power ideology. French intellectuals rushed to praise it, the leader of the surrealist group, André Breton, describing it as “nothing less than the greatest lyrical monument of our times.” In time, the poem took on classic status and is now required reading in many university courses.

Although separated by space and time, Maran and Césaire shared a similar love-hate relationship with France and Frenchness.

Both, in their different ways, served the French state, but both were outspoken critics of what they saw as its Eurocentrism and inherent racism. Both depended on the intellectual milieu of Paris for their recognition, yet each of them was an outsider and an oddity. Both condemned the cultural arrogance of France, yet both wrote in classical, lycée-learnt French.

Nor has the age-old friction between France and its Caribbean intellectuals disappeared with time. At the grand old age of 92 Aimé Césaire publicly declined to meet the controversial Nicolas Sarkozy, now President of France, during his planned 2006 visit to Martinique as Minister of the Interior. Sarkozy had recently approved a law aimed at stressing the “positive role” of French colonial policy in textbooks and other educational resources as well as describing rioting youth in French suburbs as “rabble.” The author of the Cahier remarked that “this is a trap that I am not going to fall into.” Sarkozy’s visit was cancelled.